I thoroughly enjoyed preparing the last two blog posts on Greek Music & Poetry: Ancient and Modern (Parts One and Two), and I’ve had some positive responses to that work. Thanks! I’d like, now, to stay with the general subject—the “marriage” of poetry and music—for one more post: this time with an emphasis on the thoughts of my favorite 20th century poet, Osip Mandelstam, on the topic–and attempts on the part of composers to set his poems to music.

In the best book I’ve read on Mandelstam, An Essay on the Poetry of Osip Mandelstam: God’s Grateful Guest, author Ryszard Przybylski writes, “Opinions of professional musicians about a poet’s attitude towards music should be considered authoritative,” and he goes on to cite composer Artur Sergeevich Luriye saying that Mandelstam “loved music passionately, but he never talked about this love. He kept it deeply concealed.” Przybylski concludes that Mandelstam “listened to music and said nothing about it. He said nothing and he wrote. And thanks to that writing he entered the history of Russian music.”

Here’s the cover of Przybylski’s excellent book—and two photos of Mandelstam as a young poet: (photo credits: Gregory Freidin, from his fine book, A Coat of Many Colors: Osip Mandelstam and His Mythologies of Self-Presentation, which I’ll also show here; and ralphmag.org).

We’ll take a look at what Mandelstam wrote in the way of poetry in just a moment, but first: an observation of his in prose that I found interesting: “Musical notation caresses the eye no less than music itself soothes the ear … Each measure is a little boat loaded with raisins and grapes.” Mandelstam appears to have loved everything about music—including the sight of it and even the suggested taste!

In a poem written in 1931, “Self-Portrait,” in which he makes fun of his own peculiar (verified by nearly everyone who knew him, including his wife) appearance, he says (translation by James Greene):

Here is a creature that can fly and sing, / The word malleable and flaming, /And congenital awkwardness is overcome / by inborn rhythm!

Przybylski writes, “He treated everything he did as flight and song … a poet who heard existence … who felt he was filled with rhythm, the fundamental form-creating element. He was incapable of separating poetry from music because he was incapable of separating form from content. For him art was music, which, as Boethius explained, “sometimes makes use of instruments and sometimes creates poetry.”

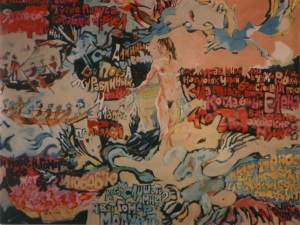

Here’s a series of drawings and woodcut prints I did myself—in homage to the various stages of Mandelstam’s life (and more about the last “stage” later):

In a poem written in 1908, the first poem in his first collection Kamen (or Stone), Mandelstam hears (Przybylski’s own translation) “The cautious and deaf sound / Of the first fruit, torn from the tree! / Amidst the resounding sound / Of the deep forest silence”; and Przybylski responds: “In the beginning there was silence. Nothingness is silence … All things arose through sound, and without sound nothing which exists would have come into being … Thus, sound is born from silence’s singing. Silence is music. This seeming paradox haunted Mandelstam throughout his life [in 1910, he wrote about a “soundless chorus of birds” that flies through “silence at midnight”] … Music, then, incorporates both silence and sound. Singing man is a form of God. The interruption of silence means the appearance of form.”

Przybylski spends considerable time on alternate theories regarding this “birth”– theories Mandelstam eventually rejected—such as Theophile Gautier’s concept of the birth of Aphrodite from ocean foam as “the birth of love,” Russian Symbolist Sergey Solovyov’s notion that she initiated a “paradise of love,” and neo-Parnassian Alexander Kondratev’ s view that Aphrodite became an emblem for “the joys of life.” Mandelstam broke with these Neo-Platonic traditions, for his Aphrodite is Anadyomede, or the one who simply “swims out of water,” and Aphrogeneia, the one “born of the ocean foam.” The Greeks believed that all births required motion and moisture (as they do )–two things “that the sea has in excess.” In another poem, “Silentium,” one of my favorites, Mandelstam sees Aphrodite as both the soul and original foundation of life, simultaneously. Here’s my own translation of “Silentium”:

It is the unborn, still— / She and the music and the word / Sustaining, unbroken /The living coherence.

Here are two classic interpretations of this moment, one the famous painting by Botticelli (“The Birth of Venus”); the other a 2nd century Roman sculpted piece: (Photo credits: waymarking.com; wikipedia.org)

Przybylski quotes musicologist Paolo Carapezza: “In ancient times music and the living logos [phonic organization of words as language] were an inseparable unit, and what is more, the former was considered to be the conscious and deliberate perfecting and refining of the latter, the revelation of it internal essence; the living logos was music in raw form, like gold in the form of ore.” Carapezza also cites a time of “esthetic transformation” when music stopped being “an extract of logos” and became “that in which the logos swims and by which it is surrounded.” Music was no longer structured on a plane equal with the word, “not according to the word,” but “appropriately according to its own patterns.” Music began to be constituted “independently of the word.”

Mandelstam, according to Przybylski, understood the meaning of this process well. In his essay “Pushkin and Scriabin,” the poet wrote: “The Hellenes did not allow music any independence: the word served them as the requisite antidote, the faithful sentinel, and the constant companion of music. Pure music was unknown to the Hellenes; it belongs completely to Christianity. The mountain lake of Christian music grew calm only after the profound transformation which turned Hellas into Europe.” And Przybylski adds, “The symbol of this unity of music and logos was, for Mandelstam, Aphrodite, but … before she swam out of the ocean foam, when she was still living in the foam or, better yet, when she was foam. For among the Greeks love was an initial movement and very quickly it became a unifying force. Thus, it fused meaning with song, intellect with rhythm, communication with expression. Thanks to love, music was born of the natural prosodic melody of the word. Each thought arose out of music, all music gave birth to thought.”

Mandelstam rejected Vladimir Solovyov’s Goethean “Eternal Feminine.” For him Aphrodite was the “primal Aphrodite, mythical, cosmogonical.”

Let my lips discover / What they cannot say: / Some crystal note / In pure birth!

For Mandelstam, ocean foam symbolized primal chaos, but not as a “negative value, an evil, or a threat.” Chaos, like silence, was “a collection of all possibilities, a prenatal anxiety, a formless proto-unity.” It was precisely this proto-unity that made it possible for the word to be “united with music.”

Again, by way of contrast, Przybylski separates Mandelstam’s beliefs regarding the marriage of music and word from those of his contemporaries and predecessors. Andrey Bely had accepted German musicologist Hanclick’s thesis that “music is a more elevated language than speech,” and Bely approved of Schopenhauer’s concept that “the esthetic priority of symphonic music, which is a ‘product of reflection,’ is completely separated from the world of phenomena, and cleansed of all contact with the word.” The Russian Symbolists praised the emancipation of “pure music,” but, according to Przybylski, a paradox existed at the foundation of their “linguistic Utopia”: the despised word had to take on the function of pure, instrumental music, which became “the highest value only because it had separated itself from the word.” Mandelstam resolved this paradox. For him, the conscious sense of the word, the Logos, was “just as magnificent a form as music is for the Symbolists.” He endorsed the wisdom of “origins.” He did not seek the essence of musicality “in an instrument, but in the word.”

Mandelstam rejected the era’s “beloved paradox” (“Yearning for wordlessness is in essence yearning for music”). He turned away from Tyutchev’s “silence as the music of the soul, deprived of the possibility of authentic communication” and even Homer (“the soul itself is a form of music, a harmonious chord”), and, unconcerned with the music of the soul, he saw “silence” existing “only in order to change formless possibility into sounding form.” Again, silence was the “expectation of sound,” “the collection of possibilities.”

O Aphrodite, remain foam! / Let words return to music, / Heart, stay heart, ashamed /If not coupled, always / With where and how you began.

Although Stravinsky never set Mandelstam to music (that I know of), Przybylski couples the two, citing the former’s “Le Sacred du Printemps,” in which he interpreted the myth “as it suited his music,” and sought primal musical material in the ancient world–a “vision of a ritual rite of the rebirth of life” in the ballet, “thanks to which man, steeped in the primitive sound of primal musical material, makes contact with the biocosmic unity.” The piece, “thanks to its ‘barbaric’ rhythms,” is transformed into “an apotheosis of sacred eroticism.” Both Stravinsky and Mandelstam sought the “same value” in primordial chaos: “Freudian Eros, the instinct of love, which supports the current of life, continually renewing the cosmos and building culture.”

Here’s a collage with Stravinsky imposed upon Henri Matisse’s painting “The Dance” (I didn’t realize how large, how monumental, this painting was, and when I first saw it, “live,” in the Hermitage, I told my wife Betty she should come back in a month or so and “rescue” me from viewing it!); scenes from “Le Sacred du Printemps,” the original production and a contemporary performance (Joffrey Ballet performance at Los Angeles Music Center); and a portion of Stravinsky’s score (Notice all those small dancing “raisins and grapes”!): (Photo credits: NPR Today; theguardian.com; huffingtonpost.com; YouTube).

In his poem “Silentium,” Mandelstam’s “silence” has a “musical character.” In his invocation to Aphrodite, if she will remain foam, the word will return to music, because “every renewal takes place only after the return to beginnings.” Mandelstam’ s “silence” was not a “criticism of language as a means of communication … primal silence was a phenomena in which form, Aprodite, is concealed.” Like Mozart, Mandelstam saw silence optimistically. Mozart “insisted” that silence was more essential than sound in music, because only in silence, “filled by mental effort, is a decisive grasping of form possible.” The “Prince of Silence,” Miles Davis, is known to have said “In music, silence is more important than sound.”

In his poem “Silentium,” Mandelstam’s “silence” has a “musical character.” In his invocation to Aphrodite, if she will remain foam, the word will return to music, because “every renewal takes place only after the return to beginnings.” Mandelstam’ s “silence” was not a “criticism of language as a means of communication … primal silence was a phenomena in which form, Aprodite, is concealed.” Like Mozart, Mandelstam saw silence optimistically. Mozart “insisted” that silence was more essential than sound in music, because only in silence, “filled by mental effort, is a decisive grasping of form possible.” The “Prince of Silence,” Miles Davis, is known to have said “In music, silence is more important than sound.”

Przybylski concludes this portion of his book by asserting that Mandelstam’s “silence” is not a “modernistic Nirvana, but the source of creation. Creation, in turn, is affirmation of life, the acceptance of the material world, the joyous sensing of things.” Mandelstam “linked his art with life, with the earth.”

Przybylski then turns his attention to a “primal abyss” that some people feel as a threat. He says “we should not be surprised that Mandelstam expressed the thought that music is unable to save us from the primal abyss. Music itself, after all, belongs to a certain extent to the abyss, because it was born out of silence … but a sound can interrupt the terror silence, it can charm the abyss. That is why the soul signifies a bursting into song. One must summon rhythm, even though it appears only rarely, like grace. Only a singing soul can create form. The poet, then, is a man in whom molino vivo, the creaking mill of life … has not destroyed his ability to sing. Creativity is a kind of song. That is why Mandelstam did not just recite his poems and did not try to force the meaning of the lines into meter. If a sentence in a poem does not fit the melody, it has no meaning. The meaning of a poem is in the music. So that Mandelstam sang his poems.”

Przybylski reminds us of a single phonograph recording of the poet “singing” a poem of his [and more about this poem at the end of this blog post], and the testimony of his contemporaries bear this out. “The wandering aoidos probably sang Homer’s epics like Mandelstam”–which reminds me of what I’ve said elsewhere about Homer as the first “anchor person,” but singing the evening news: “There was a fierce battle in Troy today,” et cetera.

“The musician is depicted in Mandelstam’s poetry as a priest entreating the abyss,” Prybylski writes, and once again, he asserts: “To create, then, means above all to create music. For the wave comes out of the sea to a measured beat … rhythm is the source of shape. A poet is a creator only when he creates musical shape. The musician is the archetype of the creator.”

Przybylski offers Mandelstam’s thoughts on Bach and Beethoven, for the poet has written a poem about each. For the poet, Przybylski claims, Bach was an artist who understood music as “the organized resistance of the spirit against the elements … Above the dust of time, above the disharmony of sounds swirling in taverns and churches, [Bach] triumphs like a new Isaiah, because Isaiah is continually proving the obvious: that God exists, that A = A.” Mandelstam himself has written, “Logic is the kingdom of the unexpected. To think logically is to be perpetually astonished. We have come to love the music of proof.” And he found such music in Bach.

The introduction of the words “logic” and “proof” after “Isaiah” and “God” made me think of an interesting book I am reading just now: physicist/saxophonist Stephon Alexander’s The Jazz of Physics: The Secret Link Between Music and The Structure of the Universe. In the Introduction, the author writes: “Contrary to the logical structure innate in physical law, in our attempts to reveal new vistas in our understanding, we often must embrace an irrational, illogical process, sometimes fraught with mistakes and improvisational thinking … The intricate way that the fundamental laws of physics work together to create and sustain the overarching structure of the universe, responsible for our very existence, seems like magic—not unlike the bare bones of music theory have given rise to everything from ‘Twinkle Twinkle Little Star’ [the “bare bones” or underpinings of the song “It’s a Wonderful World”] to Coltrane’s Intersteller Space. By using an interdisciplinary focus, inspired by three great minds (John Coltrane, Albert Einstein, and Pythagoras), we can begin to see that the ‘magical’ behavior of the blossoming cosmos is based in music.”

Here are: cover of The Jazz of Physics; Stephon Alexander at work; the cycle of fifths, and cosmic conclusions John Coltrane (literally) drew based on the cycle of fifths (a diagram he entrusted to saxophonist Yusef Latif): (photo credits: sourcesnpr.org; Miles Okazaki).

Throw in a little Galileo, Tycho Brahe, Kepler, and Richard Feynman for good measure. And within Osip Mandelstam’s inclusiveness (the “sum of opposites”: his unique blend of religion, mythology, and pagan ritual), he maintained a healthy respect for empiricism. He once wrote: “O poetry, envy crystallography, bite your nails in anger and impotence! For it is recognized that the mathematical formulas necessary for describing crystal formation are not derivable from three-dimensional space. You are denied even that element of respect which any piece of mineral crystal enjoys.” And he included the following two lines in a poem: “… here on earth, not in heaven, / as in a house filled with music.”

Mandelstam also believed the “abyss” could be controlled by an artist who was the opposite of the reasonable logical Bach: a mad, Dionysian artist like Beethoven, whose music was “a modern orgy, a holy intoxication, a momentary deification of man”–madness which allowed Beethoven, for a time, “to achieve the fullness of existence.” Przybylski adds, “On this is based Beethoven’s joy … Like an epic poet, an artist in the full sense of that word, [Beethoven] transformed his ‘I,’ that Dionysian arch-pain, into the subject of art, and sang it in Apollonian measure.” Przybylski believes that “to prove or to drive mad” is the function of art: “to lift man above his terror.” He mentions the word “panmusicality,” for he feels the world itself “has a musical character.”

So much of what Przybylski says is said in the name of Mandelstam: thoughts that derive from him or which would have met his approval. For Mandelstam, music was “divine fullness, the sum of opposites, silence and sound, primal formlessness and form, barbariousness and culture, fear and joy, terror and liberation … Mandelstam loved the logic of forms in music, but he was also fascinated by screams of pain … as a sum of antinomies, music has a divine nature. Musical form is the product of wonder, and its function is proof.”

Robert Tracy, who has translated Mandelstam’s first book, Stone, points out that the poet “only rarely” had a room of his own in which to work and write–that he usually composed his poems in his mind “while walking the streets and wrote or dictated them only at the end of the poetic process.” He cites a question Mandelstam asked regarding Dante: “How many sandals did Alighieri wear out in the course of his poetic work, wandering about on the goat paths of Italy?” Mandelstam imagined his “admired Dante sharing his own work habits”–that The Inferno and especially The Purgatorio “glorify the human gait, the measure and rhythm of walking.” And Przybylski reminds us that “that is why Beethoven also fascinated him as a walker measuring the fields and woods in the environs of Vienna.”

Here are: Dante’s first encounter with Beatrice on one of his walks (painting by Henry Holiday); and, coming up next, Terpander with his lyre (looks as if he’s playing a game of tennis!): (Photos credits: Wikipedia.org; findagrave.com)

Przybylski’s book on “God’s Grateful Guest,” contains some final thoughts on, a summary of, Mandelstam’s love of music in a chapter called “Terpander’s Lyre,” focused on a stanza from a poem, “Cherepakha” (“Turtle”), dedicated to that poet’s “Turtle lyre,” the stanza itself dedicated to musicality, that is, to “that element of poetry which Parnassus had completely forgotten” (Przybylski’s own translation):

Unhurried is the turtle-lyre / Fingerless, she just barely crawls out./ Lies about in the sunshine of Epirus / Silently warming her golden stomach. / Well, who will fondle such a one, / Who will turn over the sleeper? / She is awaiting Terpander in her sleep. / Anticipating descent of the dry fingers.

What a set of wild, sexy images; what graceful lust for an instrument made from a turtle’s shell in order to make music come alive–with the assistance of a poet’s “dry fingers” of course! Once again, Przybylski hammers home the “exceptionally high value” [highest?] that Mandelstam placed on musicality in poetry. “He was pleased that Verlaine placed “De la musique avant toute chose” [“You must have music first of all,” Verlaine adding, in the seventh and eighth lines: “Nothing more dear than the tipsy song/Where the undefined and Exact combine.”] at the beginning of his Poetic Art. Convinced that poetry’s origins are in song and that the phonetic element is more essential than the pictorial in poetry, the author of Tristia [the book in which “Turtle” appears] could not follow the path of the Parnassians, “who did not understand that admirers of Hellas cannot ignore and reject musicality … Despite the set opinions of several scholars who were fascinated by the plastic arts, it was music that occupied the central position in Greek esthetics. Among the Greeks a true creator was a poet or a musician: a sculptor was only a craftsman … according to legend, the lyre fell from heaven. It was a gift of the gods. The seven planets were compared to its seven strings. The canon of beauty was based on the numbers which the harmony of tones dictated.”

Przybylski claims that Mandelstam rose above any “artificial division” or distinction between the “Classical” and “Romantic,” that he had reached back to a tradition that was earlier than the “French error,” and arrived on his own at the genuine tradition of Classical poetry: molpe–song and dance. “The ancient Greeks’ bard was at one and the same time a leader of the dance and a director of the chorus. His poetry was not performed in isolation. Words were always tied to music and the rhythm of the dance. ‘Dance’ and ‘music’ also had a different meaning in those days, and were certainly not specialized. The ancient Greeks’ poetry was created, then, by the musically inspiration of the bard.”

Przybylski concludes: “Mandelstam linked musicality with inspiration. In his conception, music liberates in the poet thought which has been prepared by intellect … he placed a high value on … incantation, without which he could not imagine intensity of experience. The element of incantation, remaining forever in a poem, could evoke in the reader a movement of his soul, or ecstasy, which allows him to understand the poet’s thought: to recreate the creative process.”

The greatest gift that Google has ever given me is the actual voice of Osip Mandelstam. I made this discovery inadvertently, by accident, searching for something else: any and all musical settings of his poems by composers–a number of which I did find. The surprise that came up was a 1924 recording of Mandelstam himself reading his poem “No, I was never anyone’s contemporary,” this and “Tsyganka” (“Gypsy Girl”) on a Northwestern University site called “From the End to the Beginning: A Bilingual Anthology of Russian Verse,” a site that also contains several of his poems in print.

I was only partially prepared for what I heard. Here was Mandelstam himself–actually standing, reciting, no, singing, in my studio! I had previously run across various accounts of, testimonials regarding what it was like to hear him read when he was alive: his body “slightly rocking to the rhythm of the verse,” his entire face “so transformed by inspiration and self-abandonment” that, ordinarily “unassuming,” it had become “the face of a visionary and prophet.” Those attending such performances claimed they could feel “the presence of the spirit possessing the poet”; they could hear the poet’s “oracle” and experience “that which is sacred but remained concealed in ordinary life.” At one reading, Mandelstam presided as “a shaman for two and a half hours,” as if in trance. Boris Pasternak was present and was overcome by “the terrifying exorcism.”

What I heard–in spite of the heavy pops and blips and crackling that accompanied this nearly prehistoric recording–more than verified what witnesses had described: that Mandelstam did not just recite but sang his poems. He did not do so in the somewhat “singsong,” wistful, studied, somewhat theatrical style of Yeats reading “Lake Isle of Innisfree,” but in the highly urgent, instantly affecting manner of that Russian tradition that Vladimir Mayakovsky made familiar, “at the top of his voice,” and Andrei Voznesensky and Yevgeny Yevtushenko perpetuated throughout the era–the 1960s–in which they made their public readings available to listeners like me. The closest American equivalent may be our own tradition of public oratory, but Mandelstam’s purpose was never overt or all-too-obviously political or religious persuasion (the two so often combined in our culture), but the art of poetry itself. Mandelstam enunciates each syllable as if it were as round and real as his beloved stone, a phenomena sacred in and of itself–and the total result is an aria as memorable as any you might know from opera by heart (but free of the schmaltz occasionally associated with opera). Mandelstam sings the pure joy of language that embodies all that human music can contain.

After being stunned by this experience, and having played the recording over and over and over again (I didn’t want him to leave the room!), I turned my attention to composers who had attempted to set his poems within their own music: Elena Firsova (who has provided chamber cantata for solo voice and ensemble settings from the poems in Tristia through the Voronezh Notebooks–“the most tragic poems,” in her estimate by her “favorite poet,” as he is mine). Firsova comments, “From his poetry I learnt that we can speak very quietly about the most important things, and that we can see the most tragic occurrences in the light of beauty.”

Here are Mandelstam and Elena Firsova: (Photo credit: YouTube)

I also listened to Yelena Frolova’s “Russian Silver Age” settings (which includes poets Blok, Bely, Tsvetayeva, Akhmatova, and Yesenin as well as Mandelstam); Gordon Beeferman’s Now no one will listen to songs, which features “With vaguely-breathing leaves,” the last stanza of Mandelstam’s “Why is there so little music/And such silence?”; Vladimir Dukelsky’s (otherwise known as Vernon Duke) Ode Epitaphe 1931; a song cycle by Michael Zev Gordon; Giya Kanchel’s Don’t Grieve (presented by Michael Tilson-Thomas and the San Francisco Symphony, featuring Dmitri Hvorostovsky as vocalist soloist); Valentin Silvestoir’s Silent Song (six poems by Mandelstam); and a Dances for Petersburg program presented by the University of Michigan Dance Company, which offered Jessica Fogel’s “We Will Meet Again in Petersburg” (a cycle that includes that poem, “The Admiralty” and “At a terrible height”).

Some of what I’ve heard seems to carry too much self-conscious “weight” for what would be appropriate for or equal to Mandelstam’s work–an attempt on the part of the singers to out-Chaliapin Chaliapin perhaps, bypassing nuance for the sake of overlarge boulders that do not, to my mind, possess the fine resilience of the poet’s beloved stone.

A well-meaning effort that, unfortunately, suffers from this fault is Steve Lacy’s (and he’s one of my favorite jazz soprano saxophonists) Rushes, 10 Songs from Russia, which pays homage to Marina Tsvetayeva and Anna Akhmatova, as well as Mandelstam.

Here are poets Akhmatova and Tsvetayeva: (Photo credits: wikipedia.org; silveragepoetry.com)

One of Mandelstam’s poems represented is “I say this as a sketch and in a whisper,” other favorite of mine (here in David McDuff’s excellent translation):

I say this as a sketch and in a whisper / For it is not yet time: / The game of unaccountable heaven / Is achieved with experience and sweat … / And under purgatory’s temporary sky / We often forget / That the happy repository of heaven / Is a lifelong house that you can carry everywhere.

Stacy’s stated purpose was to make the poet’s words “better known,” to set the poems “without betraying their spirit, into jazz art-songs,” but my disappointment was immense when I heard what he and vocalist Irene Aebi had done with this poem–its “spirit” betrayed from the very start, to my ears: Aebi shouting, nearly screaming “I say it … in a whisper.” The conception struck me as totally contrary, at odds with the intention and tone of Mandelstam’s fine, subtle poem.

A poem previously cited (“The cautious and deaf sound / Of the first fruit, torn from the tree / Amidst the resounding sound / Of the deep forest silence”) provokes, after a handsome subtle Tracy instrumental introduction, the same sense of over-kill–of being at odds with Mandelstam’s concept of music “emerging from silence.” Another of my favorite poems (“I have the present of a body–what shall I do with it / so unique it is and so much mine.”) is rendered in French (this after Lacy, in the liner notes, has stated as a disclaimer of sorts: “The Russian language is already music”); and a very moving poem about the Terror–“Into the distance –go the mounds of people’s heads / I am growing smaller here–no one notices me anymore”–is rendered redundant through over-dramatization.

As composer, Lacy may have been too preoccupied with Mandelstam’s ultimate fate (those who know of it can’t help but feel considerable compassion), for he states, “Real jazz is dissident music. In Russia, poetry can be fatal” (which is true enough), but he goes on to say that Mandelstam was “crushed like an insect, after having brought forth a carefully preserved, full life’s work, of timeless literature.” Mandelstam’s fate was cruel (more about that in a moment), but this was a man who stood up to the regime in his poetry, who refused to succumb to “official” jargon, the trite slogans of the era (publicly pressed at a reading as to what he “believed in,” he bravely replied that he believed in “world culture,” not Soviet)—a man who believed there was nothing tougher than a human being. Osip Mandelstam was decidedly not someone “crushed like an insect.”

I’ve spent some time on what I feel is a misrepresentation of his poetry in music because it’s something one does encounter, on occasion, on the part of well-meaning composers and singers not fully “in tune” with the work itself. When that happens, I almost wish they’d just left the poem alone, and stuck with a strictly Schopenhauer “’product of pure reflection’ … cleansed of all contact with the word.”

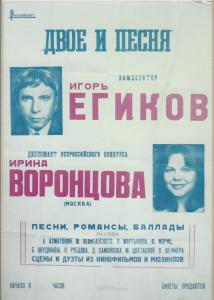

That was not at all the case with another discovery I made, again, by way of a most fortunate “accident”– another gift that made Mandelstam truly come alive for me through a marriage of poetry and music. In the summer of 1990, my wife Betty and I traveled 9,000 kilometers throughout the former Soviet Union, gathering information on and interviewing musicians for a book subsequently published: Unzipped Souls: A Jazz Journey Through the Soviet Union. We met and spent time with a host of fascinating folks–both musicians and jazz fans–but two of the most interesting and engaging musical artists were composer Igor Egikov and his wife, singer Irina Vorontsova.

Here are: the cover of my book; a poster for a “Dvoe i Pecnia” (“Two in Song”) concert by Igor and Irina, and the Novospasky Monastery (to which they took Betty and me): (Photo credit: Moscow.info)

I fell in love with the delightful Vorontsova the instant I laid eyes on her. Her face is round above Tatar cheekbones (an ancestry of which she is proud), a face framed by long hair, unzipped dark eyes beneath handsomely arched eyebrows, a small pug nose, and a generous mouth. Meeting her and Igor came about by chance. I had shown a Professor of American Literature at the University of Moscow, Irene Norikova (who was helping me translate), a booklet of photographs our son Stephen took of my own woodblock prints and paintings of Russian poems, the text included in each work. Irene was interested in my having chosen poems by Anna Akhmatova and Osip Mandelstam, for she had a friend who’d set their work to music she said, adding, “He is an excellent composer, and his wife is a famous singer.” Irene arranged for us to meet them.

Neither Irina Vorontsova nor her husband, Igor Egikov, spoke English, so we relied mostly on Irina’s cheerful disposition and devastating smile to convey the meaning of her brilliant chatter as we set out, packed into their small car; on a grand excursion to a Moscow we would otherwise never have known, ending at the Novospasky Monastery (New Monastery of the Transfiguration of the Savior) on Krutitsy Hill just above the curl of the Moscow River leading out of town (the first monastery to be founded in Moscow in the early 14th century). In spite of a slight drizzle, we strolled the grounds, Irina singing Bulat Okudzhava (my favorite Russian “troubadour” of the 1960s) songs at my request. Igor Egikov was cheerfully reticent. A pupil of Aram Khachaturian, he specializes in writing music for his wife. According to a review in the Boston Globe, when the couple performed in this country, Igor was interested “in finding a new direction for music, a third stream, that would reconcile serious classical music with popular idioms.” The Globe referred to “the vibrant Vorontsova, a world class cabaret singer,” as a woman who “talks with her eyes.” She does, so I listened.

Outside the monastery we sat in their car and drank fine Georgian wine they had given us as a gift along with a large poster announcing a concert “Dvoe i Pecnia” (“Two in Song”—the name of an album they also gave me), an evening of songs, romances, ballads and poems by Akhmatova, Okudzhava, and Marina Tsvetaeva set to music. We had insisted on sharing the wine there and then, Igor acquiring a glass, our loving cup, from one of those vile gazirovannaia voda vending machines (mineral water dispensed in cups that everyone shares, a highly suspicious rinsing device also provided). We chatted and joked, exchanging pictures of respective families, discussed art and music and life and all things under the sun as best we could with what we had by way of mutual language.

It was time for Betty and I to return to the Variety Theater for the final concert at the jazz festival we were attending. Here’s a flyer I saw posted on a wooden wall in Moscow—the event the “First International Moscow Jazz Festival”:

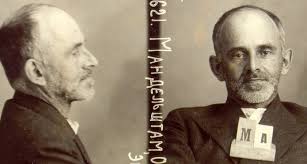

As another parting gift, Igor and Irina gave me a cassette tape with a single poem by OsipMandelstam on it, a poem entitled “Where Are They Taking Me?”, written in 1911, but a poem too prophetic, for Mandelstam would die, as a political prisoner, in a transit camp in Vladivostok in 1938 at the age of 47, initially arrested in 1934 after reciting, at a party, within earshot of a few close friends, a sixteen line poem highly unfavorable to Stalin (calling him a murderer in fact). Mandelstam’s wife, Nadezhda, in her miraculous book Hope Against Hope. suggests, in a chapter called “Who is to Blame?”, that no one person was responsible (even though they knew who turned him in), that everybody was culpable: mutual complicity, the outrageous compromise of, at that time, an entire society.

Here are: a photo of Mandelstam as a political prisoner, and another quote from his wife, Nadezhda: (Photo credit: poetrysociety,org; azquotes.com) The translation following is mine:

How slowly the horses step, / How dimly the lanterns glow. / These strangers surely know /Just where they are taking me.

And I entrust myself to them, / For I am cold. I wish only to sleep. / Suddenly, at the turning, sharp / I am thrown out among stars.

Jolted, my head swims feverously, / But icy fingers sooth me. / The dark shape of a fir tree / Lingers, out of focus.

The Russian, the language alone—as Steve Lacy recognized—is beautiful: Kak malo v fonaryakh ognya / Chuzhie lyudi, verno, znayut, / kuda vezut oni menya / A ya vreryayus ikh zabote … / Goryachey golovy kachane / nezhnyy led ruki chuzoi–and Igor and Irina transform and transmit that language with full respect. The piece opens with Igor’s solo piano vamp (in F minor), one that matches or imitates the pace of the horses perfectly–and softly, slowly, like a “dimly” lit lantern herself, Irina’s voice enters, rich with troublesome irony (“These strangers surely know / Just where they are taking me.”), fitting in light of Mandelstam’s subsequent experience, but not exploiting it. The only “content” not in the poem is her subtle and moving “ejaculations” at the end of each stanza: a single syllable, “ah,” repeated, and, before the last stanza, “oi yoi yoi yoi yo oi,” which perhaps I could have done without, but which again are fitting (“earned”) and not overly dramatic (in excess of tone and circumstance)–offered so “delicately” and inobtrusively that I feel Mandelstam himself would approve, would not object.

The couple’s interpretation of this poem is so handsomely self-contained (just like the poem itself), consistent in tone (like the poem again), the dynamics so fitting, subtle, everything so “well placed,” the economy so in keeping with Mandelstam’s intent and style (Irina’s voice disclosing maximum effect with regard to the words without impeding them in anyway), I cannot imagine their version being improved in any way. Bravo! Thank you (spasibo bolshoi), Igor Egikov and Irina Vorontsova, for showing just what can happen to a poem, emotionally, when the word, logos, is truly married to music—that balancing act Mandelstam managed so well in his work: a blend of romanticism and equilibrium, logic and a touch of madness: poetry all the more powerful for its depth expressed through economy and restraint.

I wish I could close this blog post with an example of my own attempt to set a poem by Osip Mandelstam to music, but, whereas I have set a few of my own poems that way, I have yet to find music for one of his. I do have a reading I did (on YouTube) of “No, I was never anyone’s contemporary,” which I translated. My friend, the amazing Bob Danziger, a gifted musician, composer, sound sculptor, inventor, author, entrepreneur, and a key player in the alternative energy industry for over thirty years, undertook the video project, and he asked me to participate directly. First he had me select a piece from his exceptional music project, Brandenburg 300; then, in his studio, he asked that I read Mandelstam’s poem over (and “within”) this music–to which he would add visual material (I gave him the names of Russian artists from Mandelstam’s era: Kandinsky, Malevich, Chagall, Nathan Altman’s “Portrait of Anna Akhmatova,” Levitan, Vrubel; and also, at his request, some of my own art work, a series of drawings and woodcut prints I’d done of Mandelstam and other pieces, and some photos from my own life).

Bob located excellent photos of Mandelstam (and the art work from his era)–his intent to make this video a genuine “Mandelstam and Minor” (the title of the piece) collaboration: to honor the poet and also, as he put it, the fact that I have “survived.” Bob submitted “Mandelstam and Minor: I Am No One’s Contemporary” to the 2015 International Monarch Film Festival: films to be shown at an award ceremony at the Lighthouse Cinema in Pacific Grove, California, and the film was accepted. Our homage to Mandelstam can be found at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=HxliLhcnyAY.

Here’s a “still” from the video of me reading “No, never was I anyone’s contemporary”:(Photo credit: Bob Danziger and the 2015 International Monarch Film Festival).

I’ll close with a poem of Mandelstam’s I did a painting of (“Insomnia”), the painting I stood in front of for the film–a poem I’ve also translated (and appeared in the literary journal Hanging Loose 49).

I love the line “The sea, Homer–everything is moved by love”; and that seems a perfect “note” on which to close.

I love the line “The sea, Homer–everything is moved by love”; and that seems a perfect “note” on which to close.