In preparation for this blog post, I have been taking notes on books by three very different authors, but each book leads to a compatible hypothesis (or conclusion) on their part. The authors are Jeffrey M. Schwartz (The Mind & The Brain: Neuroplasticity and the Power of Mental Force), Henry P. Stapp (Mindful Universe: Quantum Mechanics and the Participating Observer), and Dean Radin (The Conscious Universe: The Scientific Truth of Psychic Phenomena).

I concluded my last blog post by saying that, when I wrote again, I would like to address “the ongoing debate (or ‘civil war’) in the world of science between (1) materialist reductionism (‘The idea that all phenomena can be explained by the interaction and movement of material particles’) and (2) neuroplasticity (‘rewiring’ of the brain), volition, free will, bidirectional ‘causality relating brain and mind’: two opposite sides in that ‘war’ that young Isaac Newton set in motion when he got conked on the head beneath an apple tree (although even that ‘fixed’ or too perfect setting has been called into question) and Newton discovered the law of gravity, regarding our world as a windup clock–empiricism as the only means by which it can be understood, or ‘measured.’

Here are visionary artist William Blake’s painting of Sir Isaac Newton, “measuring” (In a letter, Blake wrote, “Pray God us keep/From Single vision & Newton’s Sleep”; and in a poem: “Newton’s Particles of light/Are Sands upon the Red sea’s shore”; also: “Can wisdom be put in a silver rod?”)—the second print is Blake’s “Ancient of Days,” also with compass or calipers in hand, instruments “sinister” to the poet, both literally and figuratively. (Photo credits: www.wikiart.org; wikipedia)

I concluded that post with: “‘Newton in some sense largely eliminated the divine from the ongoing workings of the universe,’ states Jeffrey M. Schwartz in his excellent book The Mind and the Brain: Neuroplasticity and the Power of Mental Force (which, along with Mario Beauregard and Denyse O’Leary’s The Spiritual Brain: A Neuroscientist’s Case for the Existence of the Soul is of considerable interest, along with [Stapp’s book]. I will save an analogy, or congruence I find with jazz for the next post—so please ‘stay tuned,’ for I hope you will find the comparison, and an account of John Beasley’s amazing interpretation and arrangements of Thelonious Monk’s work engaging, and interesting.”

So here we are, now, with some thoughts on (and quotes from) three different views of the on-going Brain/Mind controversy (classical Newtonian physics versus neuroplasticity). Jeffrey Schwartz is a research professor of psychiatry at the UCLA School of Medicine; Henry P. Stapp “has spent his entire career working in frontier areas of theoretical physics”—pursuing “extensive work pertaining to the influence of our conscious thoughts on physical processes occurring in our brains”; and Dean Radin is a parapsychology researcher, Senior Scientist at the Institute of Noetic Sciences (IONS), in Petaluma, California, and former President of the Parapsychological Association.

All three authors have focused their attention on the issue of “mind-brain” interaction, on how contemporary basic physical theory differs from classic physics, on the role of consciousness in human agents when they encounter the structure of empirical phenomena—and all three would seem to favor philosopher David J. Chalmers, when he writes about “the hard problem” of consciousness (“There is nothing that we know more intimately than conscious experience, but there is nothing that is harder to explain.”), and in his book The Character of Consciousness, Chalmers devotes 568 pages to an attempt to explain this all-too-human condition.

In cruel contrast, ethologist, evolutionary biologist and author (The Selfish Gene) Richard Dawkins attempts to resolve the issue in four succinct sentences: “We are machines built by DNA whose purpose is to make more copies of the same DNA. That is exactly what we are here for. We are machines for propagating DNA, and the propagation of DNA is a self-sustaining process. It is every living object’s sole reason for living.”

Schwartz, Stapp, and Radin–whatever their differences–spend considerable space (and words) in their books attempting to show (and support with examples) the obsolescence of mainstream (“only the physical is real”) materialism, classic Newtonian physics, Hard Science, reductionism (as quoted before: “the idea that all phenomena can be explained by the interaction and movements of material particles”)—and openly (and courageously) espouse the merits of neuroplasticity: the “ability of neurons to forge new connections, to blaze new paths through the cortex, even to assume new roles … rewiring the brain.”—or, God forbid, Free Will!

Schwartz came to his position, or vision, by way of innovative therapy sessions he worked out for patients suffering from (or locked into) obsessive/compulsive behavior—alongside an extra-curricular interest in Buddhist “mindfulness.” Schwartz quotes the following from “one Buddhist scholar”: “You’re walking in the woods and your attention is drawn to a beautiful tree or a flower. The usual human reaction is to set the mind working, ‘What a beautiful tree. I wonder how long it’s been here. I wonder how often people notice it. I should really write a poem’ [or worse: ‘I should probably cut it down for firewood!’] … The way of mindfulness would be just to see the tree … as you gaze at the tree there is nothing between you and it.” Schwartz adds, “There is full awareness without running commentary. You are just watching, observing all facts, both inner and outer, very closely.” You are just living the tree?

Here are David J. Chalmers’ The Character of Consciousness; Jeffrey M. Schwartz’s The Mind and the Brain: Neuroplasticity and the Power of Mental Force; and a photo of Schwartz himself. (Photo credit: Goodreads)

Here are some other observations by Jeffrey Schwartz I appreciated: “Individuals choose what they will attend to [two of his favorite words are “awareness” and “attention” (“intended action!”)]… Science ceded the soul and the conscious mind to religion and kept the material world to itself … By choosing whether and/or how to focus on the various possible states, the mind influences which one of them comes into being … The triumphant idea can then make the body move, and through associated neuroplastic changes, alter the brain circuitry … Radical attempts to view the world as a merely material domain, devoid of mind as an active force, neglect the very powers that define humankind … The science emerging with the new century tells us that we are not the children of matter alone, nor its slaves.”

He also praises (for its far ahead of its time insight), the words of William James: “Nature in her unfathomable designs has mixed us of clay and fire, of brain and mind, that the two things hang indubitably together and determine each other’s being.”

Jeffrey Schwartz is also fond of quoting his friend (and eventual collaborator) Henry Stapp: “the replacement of the ideas of classical physics by the ideas of quantum physics completely changes the complexion of the mind-brain dichotomy, of the connection between mind and brain … In quantum theory, experience is an essential reality, and matter is viewed as a response then of the primary reality, which is experience.”

Henry P. Stapp’s prose style is, overall, more technical, demanding, and, although of considerable interest, perhaps less accessible at times (to someone like me, a definite “layman”), but he is dealing with the subject about which the renowned physicist Richard Feynman confessed (in his series of The Character of Physical Law lectures), “I think I can safely say that nobody understands quantum mechanics.” Stapp would hope to convince you otherwise, commencing the Preface to Mindful Universe: Quantum Mechanics and the Participating Observer with these words: “The new theory departs from the old one in many important ways, but none is more significant in the realm of human affairs than the role it assigns to your conscious choices.”

Stapp cites a “tremendous burgeoning of interest in the problem of consciousness” now in progress, and quotes from an article by neuroscientist Antonio Damasio: “At the start of the new millennium, it is apparent that one question towers above all others in the life sciences: How does the set of processes we call mind emerge from the activity of the organ we call brain?” Damasio answers his own question: “I contend that the biological processes […] now presumed to correspond to mind in fact are mind processes and will be seen to be so when understood in sufficient detail”—and he hints that biological processes “understood in sufficient detail” are really “quantum understanding.”

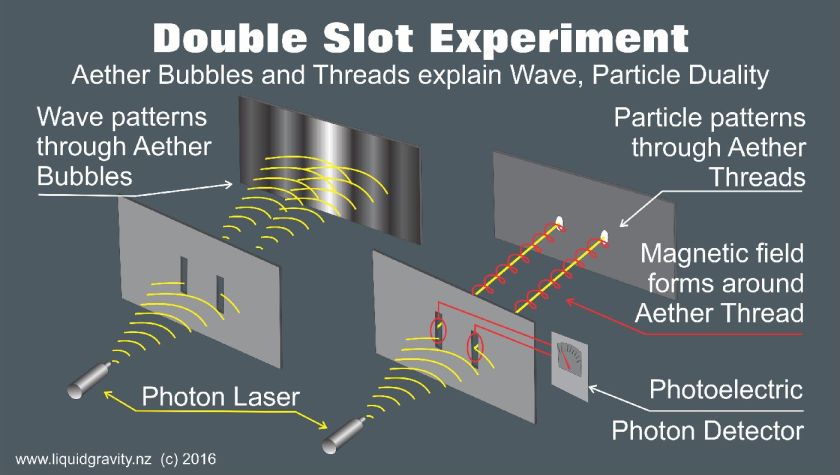

Enter Henry P. Stapp with his “deep interest in the quantum measurement problem.” His own book is loaded with vital information on (and understanding of) every phase of quantum theory from the fundamental role of the observer; the wave/particle phenomena; placebos; the locality/nonlocality issue; Einstein’s “Spooky Action at a Distance”; the Quantum Zero effect—a host of aspects of the two co-existing parallel mental realities; and even an extensive analysis of Alfred North Whitehead’s thoughts, one of the first mathematician/philosophers to comprehend quantum mechanics and incorporate its theories into his organic philosophy and Process Ontology.

Here is a photo of Henry P. Stapp, and the cover of his book, The Mindful Universe. (Photo credit: Alchetron.com)

I won’t try to do justice to all I found of interest and value in those sections (Much!), but a chapter and material that followed is devoted to “The Impact of Quantum Mechanics on Human Values,” and Stapp states, “The quantum concept of man, being based on objective science equally available to all … has the potential to undergird a universal system of basic values suitable to all people, without regard to the accidents of their origins”—and would thus provide “material benefits,” in every area from ethics to medicine.

Among the advantages, Stapp lists: “consciously experienced intentional choices,” “a foundation for understanding the co-evolution of mind and brain,” “free will of the kind needed to undergird ethical theory,” and improved “self-image … with consciousness an active component of a deeply interconnected world process that is responsive to value-based human judgments … Behavior, insofar as it concerns ethics, is guided by conscious reflection and evaluation … one’s weighing of the welfare of the whole.”

If “attention” (“intended action”) was a favorite, a key word for Schwartz, “interconnection” is the choice of Henry Stapp. He has a Utopian vision. EVERYTHING is interconnected! Without being fully aware of it, we are ALL (people and particles alike!) intimately interconnected—always! We are truly the molecular, and otherwise, music of the spheres, uniting medieval cosmology and NOW. His vision of and for the future is not “systematic,” and the structure of his book is loose; the book—although divided up into “chapters,” seems to float, from section to section, agreeably, as inclusive as quantum theory itself, with ease and unpredictability (Heisenberg’s “uncertainty principle” at play), enjoying its own playful quantum “jumps.” Another frequently employed word is “dynamics”—and nothing is preserved in stone, set forever, or lasting (as Newton’s classic physics did) for three centuries; all is in flux (I once wrote a poem that began: “I flux, you flux, everybody flux flux.”).

Stapp states: “According to the new conception, the physically described world is built not out of bits of matter, as matter was understood in the nineteenth century, but out of objective tendencies—potentialities—for certain discrete, whole actual events to occur … This coordination of the aspects of the theory that are described in physical/mathematical terms with aspects that are described in psychological [subjective] terms is what makes the theory practically useful. Some empirical predictions have been verified to the incredible accuracy of one part in a hundred million.”

Here are photos of: quantum mechanics equations and the wave/particle double slot experiment. Photo credits: www.thoughtco.com; http://www.liquidgravity.nz)

“Mindfulness” (attention, interconnectedness) would seem to be the order of the day.

Although Dean Radin shares conclusions and convictions with Schwartz and Stapp, he comes at the mind-brain dilemma from a slightly different angle or perspective: defending his field of specialty (parapsychology) from constant attack or criticism on the part of hard science, which regards the study of the mental phenomena he has devoted his life to as inexplicable—or an illusion.

His book–The Conscious Universe: the Scientific Truth of Psychic Phenomena—is systematic: a carefully sequenced argument, or act of persuasion, from the Preface (“When we set out to prove the boundaries of consciousness and reality … it is essential to cultivate tolerance for the unexpected”) to the book’s “wrap up” on page 339: “Future generations will undoubtedly look back upon the twentieth century with a certain poignancy. Our progeny will shake their heads with disbelief over the arrogance we displayed in our misunderstanding of nature. It took three hundred years of hard-won scientific advances merely to verify the existence of something that people had been experiencing for millennia.”

Radin is devoted to noetic (from the Greek word “noesis” or “noetikos”: intuition or inner wisdom, direct knowing, subjective understanding) science: a branch that employs rigorous scientific methods with multidisciplinary scholarship in the study of what philosopher William James (far-seeing in 1902) referred to as “states of insight into depths of truth unplumbed by the discursive intellect.” Using this method Radin recognized (discussed under the heading “Belief Becomes Biology” in his book) that an external suggestion can become “an internal expectation” that can “manifest in the physical body”–the implication being that the body’s “hard physical reality can be significantly modified by the more evanescent reality of the mind.”

Radin offers sections of text that carefully, and clearly, define such phenomena as telepathy, clairvoyance, psychokinesis, precognition, ESP, out-of-body experience, near-death experience, and reincarnation. He feels that, in spite of the fact that such states have been in existence (with much evidence of them) “for millennia,” science itself has evolved into the absurd position of “the mind denying its own existence” (“Science has effectively lost its mind.”), and he believes that underlying the world of ordinary objects and human experience “is another reality, an interconnected world of intermingling relationship and possibilities”—an underlying reality “more fundamental–in the sense of being the ground state from which everything originates—than the transient forms and dynamic relationships of familiar experience.”

Here is Dean Radin, and the cover of his book The Conscious Universe. (Photo credit: http://www.deanradin.com)

I like a witticism Radin attributes to physicist Nick Herbert, who makes the claim (along with other writers we’ve encountered) that consciousness is our “biggest mystery,” but adds: “it is not that we possess bad or imperfect theories of human awareness, we simply have no sense of them at all. About all we know about consciousness is that it has something to do with the head, rather than the feet.”

Henry P. Stapp’s favored concept, “interconnection,” shows up again. In support for his case or stance, Radin quotes Teilhard de Chardin: “The farther and more deeply we penetrate into matter, by means of increasingly powerful methods, the more we are confounded by the interdependence of its parts … All around us, as far as the eye can see, the universe holds together, and only one way of considering it is really possible, that is, to take it as a whole, in one piece.” And Radin quotes Sogyal Rinpoche (The Tibetan Book of Living and Dying): “Everything is inextricably interrelated. We come to realize that we are responsible for everything we do, say, or think, responsible in fact for ourselves, everyone and everything else, and the entire universe.”

Radin likes the word “uni-verse”: a connected world, “not a set of isolated fragments,” which suggests another responsibility (or creative challenge) entailed: “We all carry ideas about who we are, or who we have been taught to believe we are … not only is our perception of the world a construction, but also our sense of who we think we are.”

For all his idealism, Dean Radin’s book is not devoid of practical application. In a section dealing with such (with a heading, “Medicine”), he writes, “We envison that future experiments will continue to confirm that distant mental healing is not only real, but is clinically useful in treating certain physical and mental illnesses.” And he closes on a hopeful note: ‘A society that consciously uses precognitive information to guide the future is one that is realizing true freedom … This would allow us to create the future as we wish, rather than blindly follow a predetermined course through our ignorance.”

Thus spake Jeffrey M. Schwartz, Henry P. Stapp, and Dean Radin. Before we move on to “jazz” (and applying some of these theories to the art of improvisation), I’d like to cite a final passage from another book I mentioned in passing: The Spiritual Brain: A Neuroscientist’s Case for the Existence of the Soul—a book whose final vision for the future contains even larger aspiration than the others I’ve discussed: “Mystical experience from various spiritual traditions indicates that the nature of the mind, consciousness, and reality as well as the meaning of life can be apprehended through an intuitive, unitive, and experiential form of knowing … The proposed new scientific frame of reference may accelerate our understanding of this process of spiritualization and significantly contribute to the emergence of a planetary type of consciousness. The development of this type of consciousness is absolutely essential if humanity is to successfully solve the global crises that confront us … and wisely create a future that benefits all humans and all forms of life on planet earth.”

Here’s my own “take” on the mind/brain drama: I tend to get frustrated, and feel quite helpless, when a “machine” I own (such as the laptop I am working on just now; or a blood pressure monitor, or even the kitchen toaster) doesn’t function as it should (James Thurber quipped, “Machines don’t like me!”), so if I am a machine myself (as classic Newtonian physics claims), and I don’t function well (which happens from time to time—maybe I should say often!), it’s no wonder I spend (precious, hopefully potentially productive) time being upset. On the other hand, Quantum theory allows us to live our lives in the moment as it is, whatever it is or may be (being and becoming), no matter what matter it’s made of (rim shot!), and we truly need to take this gift, this moment in time–and ourselves–just as we find it (and ourselves!), and make the best of it. The same holds true for the external world, not just our internal existence—for the two are One.

So what does any of this have to do with jazz improvisation? Well … everything! The best “ingredients” of quantum physics can be found in the best jazz—when both are moving, grooving as they should: interconnected, mindful, intuitive, unitive, and experiential. Which brings us to the wondrous world–or universe–of jazz itself (at last, you may quip, and I don’t blame you!). I was ready, I was “up,” for the 60th Monterey Jazz Festival, because I was eager to see and hear a group I had heard (and read) “good things” about: John Beasley’s MONK’estra.

Journalist Willard Jenkins interviewed Beasley regarding his fresh, brilliant, innovative (all the things Thelonious Monk himself was!) arrangements of the music, and Willard quoted Beasley: “The germ of MONK’estra started with my desire to experiment with 21st century harmony for big band that swings and grooves … I started reimagining Monk’s “Epistrophy” and quickly realized that his music was the perfect match for this. The swing is already written in and since his music is very pliable, I found that I could stretch my imagination.”

Willard Jenkins adds, “John Beasley has done a marvelous job of contemporizing Thelonious Monk’s music”—and Beasley himself continues: “I compare Monk’s music to how the public must have felt upon its first view of Cubist art by Pablo Picasso, which revolutionized modern art.” I agree, because, whereas I was fascinated when I first heard Monk play, I couldn’t grasp what he was up to, and resisted it—the way that he was revolutionizing jazz. Beasley says, “On the eve of his centennial it is evident that we have finally caught up to where he was taking us.”

Here’s a photo of John Beasley and the full MONK’estra aggregate—and a photo in performance. (Photo credits: www.laweekly.com; http://www.montereyjazzfestival.org)

At the Monterey Jazz Festival, MONK’estra performed on Sunday afternoon. I wasn’t quite sure what to expect, but took notes from the start on what I heard: a not just swinging, grooving big band, but one that rocked (fully inclusive, with a surprising backbeat)—an ultra-tight ensemble, with powerful section work to support (surround and enhance) soloists who offered their share of funky licks: a little bit of everything (trying all the options on for size, simultaneously, something for everyone, like Henry Stapp’s “universal system of basic values suitable to all people, without regard to the accidents of their origins”: Quantum Physics!); a host of Monk tunes, a medly seemingly undifferentiated, a continuous suite of Thelonious. I didn’t bother to write down the titles. I just dug the tunes as a truly handsome bunch, and the full range of interpretation and improvised ingenuity based on the originals: explosive dynamics (deep growling baritone sax: Adam Schroeder; wailing trombone: Francisco Torres; altruistic alto sax: Bob Sheppard); fulsome ensemble support or “fill”; luscious unison work; luminous orchestration (as if John Beasley, like Hector Berlioz, who wrote the book on it, knows the exact timbre, texture of each and every instrument—and the best combinations or match ups); each separate melody or “head” the genesis of the next—and the truly recognizable (some of my favorite Monk tunes, “Pannonica,” “I Mean You,” “Ugly Beauty,” “Gallop’s Gallop”) emerging with all their grace and style.

Few of the tunes were announced (if I remember correctly) throughout (Beasley slipped over to the keyboards himself, unobtrusively, for “Pannonica”): just a perfectly put together wild wonderful onslaught of Thelonious, with glimpses of counterpoint, blues vamp, more than just a little “Latin touch,” a wire brush percussive break, smooth liquid sequences building to a full force orchestral flourish, and close out.

Something I realized, writing those last two paragraphs now, is that I could supplement many phrases of description with Quantum Theory “fill”—as if John Beasley’s continuous suite had been composed on Quantum principles, for it was rift with the distinct flow of particles acting as waves, nonlocal “instantaneous action at a distance,” music fully grounded in itself (its own nature, its affinity with natural life: free of the tendency of free jazz straining, trying too hard, at times, to be “free,” yet free, also, of the tendency of big bands to get locked into mandatory, or obligatory concord or unity; this group was just MONK’estra, itself, having a grand Quantum Monk time!): its music a fully present “fact,” in the Alfred North Whitehead sense of the “preeminence of congruence” established “over the indefinite herd of other such relations”—music intimately interconnected, at one with itself: music, in Henry Stapp’s words, “guided by conscious reflection and evaluation … one’s weighing of the welfare of the whole”—abundantly laced with joyous “mindfulness,” John Beasley has fulfilled his desire, his intent “to stretch [his] imagination” and, on the eve of Thelonious Monk’s centennial, “to finally [get] caught up to where he was taking us.”

Here are two geniuses side by side: Thelonious Monk and Alfred North Whitehead (Photo credit: www.burtglinn.com)

I had two enjoyable encounters following the exceptional MONK’estra set. I stopped at a long table set up on the grounds, and had a Brother Thelonious Belgian Style Abbey Ale (North Coast Brewing has donated over $1 million from proceeds of the sale of the beer and gear to support the Jazz education programs of the Thelonious Monk Institute of Jazz.). Standing next to me was a very short man dressed like Harlequin, an outrageous costume. I’d done some work for the 60th Monterey Jazz Festival (copy for an exhibit of historical posters, “Monterey at 60: A Visual Feast,” and a series of humorous historical anecdotes included in a video shown at several venues that weekend), and I was wearing what prompted my just-made friend to say, “Your badge would suggest you are a person of some importance.” Ironically, at that moment, one of my anecdotal “slides” appeared on a large screen in a pavilion adjacent to us that had couches and chairs and served drinks—so I told my new friend and his companions about my work for the Festival, and said, “Look, that’s one of mine.” They seemed impressed and asked for my card, which I gave them, and they all promised, on the spot, to buy all three of my jazz books—claiming, “Why, you yourself are living history! And you look like a writer!”

Here’s an example of one of my anecdotal “slides” (on an appearance at the MJF by Miles Davis) and the poster for the 60th Monterey Jazz Festival:

The encounter was good fun, but the next one was even better. I set out for the North Coast Brewing pavilion, to meet a journalist friend, Dan Ouellette (who conducts the DownBeat Blindfold Test each year at the MJF), and who should he be talking to when I arrived but John Beasley himself, who’d retired there with nearly his entire orchestra after their set. Dan has written about John, so he introduced me, and we sat together for … a Brother Thelonious Belgian Style Abbey Ale, of course!

Fifty-eight year old Shreveport, Louisiana born John Beasley has a (Southern?) gentlemanly presence, well abetted by urban studio work savvy (He was lead arranger for American Idol for eleven years), and a genuine genial jazz musician’s “cool” manner. You might say he’s very quantum inclusive! I enjoyed talking with him, much! I told him about my own experience as fully undeserving house pianist at a place called the 456 Club in Brooklyn in 1956 (when I attended Pratt Institute), and meeting classical and jazz composer, arranger, and pianist Hal Overton there. It was Overton whom Thelonious Monk selected to score his piano works for orchestra; a performance of these compositions recorded live in 1959 (and released as The Thelonious Monk Orchestra at Town Hall).In 1963, Monk recorded a second live album with orchestral arrangements by Overton at the New York Philharmonic Hall, released as Big Band and Quartet in Concert.

Here are the two Monk CDs for which Hall Overton provided arrangements:

John Beasley seemed interested, and even asked if I would give him my card (“Living history,” and Wow, I’d now handed out two of my “business” cards in one hour!). I even told John that I’d had a cabaret card in New York City when Monk couldn’t get one (he’d ben arrested on an extremely questionable charge of “possession,” and not only confined for sixty days in prison, but the New York State Liquor Authority removed his cabaret card, without which you could not get hired for local club dates.) He was reinstated in 1957. He was on the cover of Time magazine in 1964.

John Beasley’s own life, and career, is fascinating. He grew up in a musical family. His grandfather, Rule Oliver, played trombone in territory bands; his mother, Lida, taught music in public schools and colleges, as well as conducting operas (she earned a local Emmy for her work in Faust). John’s father, another Rule, is a pianist and bassoonist who played with the Fort Worth Symphony, and was a professor of music at two colleges. John Beasley learned to play trumpet, oboe, drums, saxophone, flute—and jazz piano, for which he is best known now, along with his arranging)—and he went on to record and perform with Miles Davis, Sergio Mendes, Steely Dan, Dianne Reeves, and James Brown. John became musical director for the Thelonious Monk Institute Tribute and International Jazz Day concerts, and has been nominated for an Emmy Award and three times for a Grammy for three different albums.

He claims he “always had a thing for Thelonious Monk,” and in 2012, he wrote a big-band chart for “Epistrophy,” then “Ask Me Now.” He formed a 15-piece band composed of top West Coast musicians, and has released two MONK’estra recordings. Here they are:

Thelonious Monk’s son T.S. has stated, “My father would have approved.” Writer Neil Tessler comments on Beasley’s “refreshing 21st century take on the ever new music” of Monk, and praises the arranger’s solid “link to the composer’s vision,” exceptional “orchestral writing,” and even Beasley’s willingness to “spark some controversy” (“using darkened harmonies and backbeat rhythms,” “a tonal pallet reminiscent of neo-soul,” on a familiar tune such as “’Round Midnight”). Tessler writes that the arranger “has deftly pulled [“Midnight”] into the orbit of modern listeners … has simply returned this song to its roots, with a conceptual twist that simultaneously makes it fresh.” Beasley has created “an entire collection of excitingly re-conceived and marvelously executed compositions.”

Elsewhere, Tessler has written that Beasley possesses “a willingness to engage these compositions with an ingenuity as audacious as the one that created them.” John Beasley’s “lifelong love of arranging” has made it possible for him to take Monk’s music, so open “to interpretation,” and enhance it with (in his own words) his own “architecture,” going well beyond “the idea of theme-solos-theme,” because, “like all great songs, Monk’s songs lend themselves to a more personal interpretation, especially when it comes to arranging.” Tessler adds, “Maybe Beasley’s affinity for Monk was simply meant to be. Monk was born October 10 in 1917; 43 years later to the day, Beasley showed up.”

I’m grateful that he did: not only in this life and for the sake of jazz, but, selfishly for my own sake, for that Sunday afternoon MONK’estra set at the 60th Monterey Jazz Festival, and for the excellent conversation I had with him after, over Brother Thelonious Belgian Style Abbey Ale! Thank you, Dan Ouellette, for introducing us—and thank you, John Beasley, for all you have given us by way of music.

I love writing this blog—the quantum “freedom” of it (when I can find time and presence of mind to do so), and if you’d told me years ago that I would someday put together an “informal essay” that combined an examination of quantum theory with an account of a first-rate jazz performance, I would more than likely have thought you crazy. So thanks for being a bit crazy in a manner to inspire me now! I look forward to surprising you (again?) with my next blog post, whenever it happens and whatever it’s about (the “uncertainty principle” again).