Jazz vocalist/lyricist Kurt Elling is gifted–along with a great voice–with an inclusive mind (and heart) that can look forward, in terms of “making progress,” to perpetual development (“The point is to keep making progress, to outdo yourself, and to keep, as much as you can, scoring a personal best.”) at the same time he remains fully “informed” by the past, by previous attainment—both his own and that of those who made (in Kurt’s words) “the greatest music that came before us.” He states: “It’s not just respect; it’s a desire to appreciate the greatest ideas. Because how else are you gonna play them? The wealth that’s come before us is such a treasure.”

Two articles on Kurt Elling have appeared recently: one in JazzTimes by Lee Mergner, another in DownBeat by Allen Morrison. Both writers focus on Elling’s latest album, The Questions. Morrison calls it “a thoughtfully curated and wide-ranging collection of songs”; Mergner directs attention to the vocalist/lyricist’s finding “in poetry, the challenge of being compassionate in a troubled world and the importance of asking unanswerable questions.” Morrison addresses the latter situation by saying, “In the current age of anxiety, Elling might not have all the answers, but his baritone voice has a reassuring quality that makes the listener feel less alone in the quest.”

Both writers cite Elling’s collaboration with saxophonist Branford Marsalis, who co-produced The Questions; the “tuneful and melodic” nature of the album; the fact that it opens with Bob Dylan’s “A Hard Rain’s A-Gonna Fall”; and the fortunate assistance, on piano, of Stu Minditon as a “secret weapon,” who says, “Kurt and I have a mutual interest in the connection between poetry and music, and he takes a poet’s approach to setting his lyrics to music.” And each writer conducts an interview that’s loaded with Elling’s customary fully articulate and insightful responses.

Here is the cover of The Questions, and Branford Marsalis and Kurt Elling side by side—co-producers of the new CD. (Photo credit: The Mercury News)

Asked by Morrison about struggling “a bit” with “stage presence” earlier in his career, and how he “came out of that phase,” Kurt Elling replied: “Keep living. That’s why I keep thinking about [age] 70. There were so many things I wanted to be. I was in love with [jazz] history, the recordings, and I wanted to be that. At a certain point you realize you’re not going to be that, you’re going to be you. But informed by all that.” And on working with Branford Marsalis: “We’re here to play great melodies and express authentic emotions—to be the real deal as much as we can … [which] means continually investigating the greatest music that came before us.” Marsalis introduced Kurt Elling to another source of inspiration: “Der Rosenkavalier,” by Richard Strauss (which happens to be just about my favorite opera) and at first, the vocalist found the music “tough listening,” but decided “If you want to understand the sound of something, then you’ve got to listen to it until you understand it.”

Kurt Elling’s passion for such discoveries, or influences, has not subsided, but increased incrementally, whereas many of his basic attitudes toward the music in general (and early influences) remain the same, rewardingly persistent, continuous (especially in an era such as ours, when so many people seem willing to try just about any old thing “on for size,” then toss it aside). The continuity, the fidelity, of his approach couldn’t help but remind me of an extensive interview I had with him back in 2009, when we focused, at the start, on his interest in the Beat Generation—a cultural phenomenon of which I was fortunate (arriving in San Francisco from Hawaii in 1958) to be a small part.

I would like, in this blog post, to reproduce the article that resulted from a five part blog I offered from 2009 to 2010 on JazzWest.com—the complete article composed over time and consisting of the following parts: Posted on July 28, 2010:”Kurt Elling and the Beat Generation, Part 5: The Ballads”; March 24, 2010: “Kurt Elling and the Beat Generation, Part 4: The Interview, Concluded”; Posted on November 17, 2009: “Kurt Elling and the Beat Generation, Part 3: The Interview”; Posted on September 16, 2009: “Kurt Elling, the Beat Generation & the Monterey Jazz Festival, Part 2”; Posted on September 8, 2009: “Kurt Elling, the Beat Generation & the Monterey Jazz Festival.”

And so, without further ado, here’s the complete essay:

When I first heard jazz vocalist Kurt Elling on two early CDs–Close Your Eyes (1995) and The Messenger (1997)–several tracks prompted an immediate “shock of recognition,” as if they were unique re-enactments of themes and preoccupations I was familiar with. I then came across articles that mentioned Elling’s fondness for and indebtedness to the Beat Generation, but I couldn’t find an article that fully explored this interesting “collaboration.” (Elling is age forty-four; the Beats considerably older.) Having arrived in San Francisco in 1958 and–thanks to the “accident” of having landed in the right place at the right time–being a part of that era, I decided to explore Elling’s connection. I don’t think you need to have once been a “Beatnik” to appreciate the full effect of Kurt Elling’s vocal style and its content, but it doesn’t hurt.

Here are the covers of Close Your Eyes and The Messenger.

On “Dolores Dream” (on Close Your Eyes), he provided lyrics to a Wayne Shorter solo intro that reminded me–albeit this Chicago-based, not San Francisco–of poetry I had once absorbed: “The white electric skillet of a day threatened to sear us all away—fat frying. Spluttering, rank Chicago smeltering along. Smothered in heavy wooly sweat, the city knew a sad regret.” Unaccompanied, Elling said/sang these lines, then introduced a set groove on the words “jump in my car, Uptown to scram. Popped in a great Von Freeman jam—and the coffee hit. Bam!”—the music replete with pulsing Laurence Hobgood piano and fast on his feet (or tongue) Elling scat. The piece ended, “If there’s one girl I’ve got to remember, it’s … it’s … it’s [aspirated] … her.” Wow, I thought: very bright, hip (“Beat”) storytelling in song—which is something, a legacy, I happen to love.

Fran Landesman’s 1950s collaboration with composer Tommy Wolf, “The Ballad of the Sad Young Men,” could, as sung by Kurt Elling, be a Beat Generation early anthem: “All the news is bad again … kiss your dreams goodbye … drinking up the night, trying not to drown … choking on their youth.” “Those Clouds Are Heavy, You Dig?” combines the Brubeck/Desmond take on “Balcony Rock” with words based on the work of another familiar figure (albeit Czech-German, not “Beat”), Rainer Maria Rilke. It’s a fable turned hip by Kurt, a “little cloud” searching for God (parents are only interested in “possessing things,” and offer useless advice, “You’ll grow out of it soon and start singing a grownup tune”); whereas “Now It Is Time That Gods Came Walking Out,” a poem by Rilke, is recited by Kurt, reflecting his concerns as a former divinity student: “Once again let it be your morning, gods …You alone are source.”

When I first listened to The Messenger, I recognized the inspiration of Thomas Merton, another mid-50s–The Seven Storey Mountain and The Sign of Jonas–influence on my life. At the time, I seriously considered becoming a Trappist monk, until a young woman named Mary Jane McLaughlin saved me from that fate. “The Beauty of All Things” is serenely, handsomely rendered with a loving piano backdrop: “There is something within you … don’t be shocked or surprised if I lift your disguise.” Eden Ahbez’s “Nature Boy” (I remember seeing a photo spread on this first “Beatnik” in Life magazine!) is enlivened, after its Nat “King” Cole tempered start, by wild scat on Kurt’s part—overt risk-taking and innovation an early hallmark of his approach.

I enjoyed all ten minutes and seventeen seconds of “Tanya Jean,” a swinging vamp piece of epic extension, a track that moved from “Dig with me this chick lording every clique” (a “royal queen” who stops every clock and keeps a “flock” of men) to familiar lingo–“Dig what I’m saying”—and syntax: “unnameable surgings of lust into what must always be,” “inner vision crying into the vortex of night,” “everything always is,” “screaming across the open plains of nothingness”—Herman Hesse, another cultural icon of that time, getting in the act along with Tanya Jean, the music itself based on an extended Dexter Gordon solo.

And finally: the great good fun of “It’s Just a Thing,” with its homage to Lord Buckley of “The Naz” notoriety (“Look at all you Cats and Kittens out there!”), Kurt Elling telling a Hammett/Chandler–with perhaps a sniff of the wild raw humor of Elmore Leonard’s Tishomingo Blues?–tale, in the vernacular again: “hip to the scene,” “solid gone,” “indelibly groovevatude.”

I’d like, if I may, to extend our common cause by offering my own Beat Generation credentials, in the hope of providing that link to Elling’s accomplishments. My wife Betty and I arrived in San Francisco in 1958. We’d been married, “Bohemian” style, in Hawaii, and spent a honeymoon summer living on the only open spot on the Wailua River in Kauai, pre-statehood (the island having retained its 19th century plantation life ambiance). Just twenty-one years of age, we lived in a shack (wooden, not grass), surrounded by mangoes, papaya, bananas, and an abundance of crawfish in the river. City kids by way of background, we really didn’t have a clue as to what to do with it all. I’d known a touch of “Zen” in Brooklyn (where I’d attended Pratt Institute) by way of J.D. Salinger and the appropriately small Peter Pauper Press book Japanese Haiku, with its delicate “icons” set beside each poem by Issa, Basho and Buson. On Kauai, my interest in the culture of Japan grew by way of a movie theater that showed Japanese samurai films– without subtitles.

Here’s a photo of my wife Betty and our host that summer in Kauai, Mr. Isenberg—both eating pineapple in front of our “shack” (Betty calls it a “cabin”) on the Wailua River—and a photo of my beautiful smiling 21-year-old bride at that time.

Arriving back on the Mainland (as it was then called), we took a third floor apartment on Hayes Street in San Francisco, for $60 a month rent (jobless, I told the landlord I was a clerk in a law office, and ended up working as an elevator operator at the White House Department Store). Poet and Beat Generation pater familias (although somewhat ambivalent about his role as “guru and ringleader”) Kenneth Rexroth lived just around the corner, on Scott Street. In the liner notes to Flirting with Twilight, speaking of the lyrics he wrote to Fred Simon’s “While You Are Mine,” Kurt Elling told writer Zan Stewart, “At the time I wrote the lyric, I was reading a lot of Kenneth Rexroth, so it’s kind of a Rexroth homage. He was always aware of the passing of time, how much is irreplaceable when it’s gone, how much of life you have to get now. Now, today, baby, make it real now, especially with romance. That makes everything so sweet and bittersweet, even at the moment of the most profound togetherness.” On his first CD, Close Your Eyes, Kurt recited, surrounded by wild improvisation provided by Laurence Hobgood, Rexroth’s poem “Married Blues” (“I didn’t want it, you wanted it. Now you’ve got it you don’t like it. You can’t get out of it now … too poor for the movies, too tired to love.”)

Kurt Elling “says” this poem in a deliberately squeaky, nasal, hectored, nearly hen-pecked, all too “married” voice. The liner notes to Close Your Eyes cite Rexroth as “one of the great American intellects of the 20th Century,” playing “a pivotal role in the San Francisco literary revival”—which is true. When I first tried my hand at poetry, I was strongly influenced by the spare, straightforward strength and brittle beauty of his book The Signature of All Things and his splendid One Hundred Poems from the Japanese. Yet, ironically, Rexroth’s own voice does not come across as all that impressive. I recall being enthralled by the content (and daring) of his performance at the Cellar, reading (to jazz) “Thou Shalt Not Kill” (in memory of Dylan Thomas: “You killed him/In your God damned Brooks Brothers Suit”), but I will confess that, in spite of the sublime nature of much of his poetry, his own pre-“Howl” rant against 1950s unhip bourgeois America—Timor mortis conturbat me (“the fear of death disturbs me”) indeed!—strikes me, today, as comical, pretentious. Rexroth sounds a bit squeaky, nasal, hectored himself, although his was one of the early, experimental efforts to merge, or marry, spoken word and jazz.

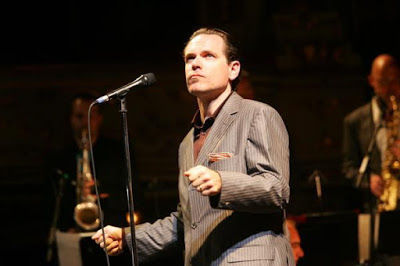

Here is a photo of Kenneth Rexroth reading, or “jammin,’” with musicians—and Kurt doing his thing with a mic before an audience. (Photo credit: http://www.foundsf.org and http://www.minnpost.com)

Kurt Elling is one of the more expansive, inclusive, flexible jazz artists I’ve ever run across, and I would like to pay homage to what’s been said, and written–and what he’s said himself–about that versatility, his wide range of musical activity (“A man of enough parts to be a faculty unto himself”), activity made up of consummate showmanship (“continually taking chances and coming up with fresh approaches”), a solid work ethic (“nonstop weekend for him at the Monterey Jazz Festival”—when he was Artist-in-Residence there in 2006); creativity (from himself: “The daily discipline it takes to see the world with fresh eyes and to try to approach everything that’s coming to you as a potential gift, there’s poetry in that.”); experimenting with vocalese (“a chance-taking improviser who often makes up lyrics as he goes along”), his having been a graduate student at the University of Chicago Divinity School (“Make a joyful noise unto the Lord, all ye lands … and come before his presence with a song;” well, he didn’t write that: that’s Psalm 100, but he has said, “Jazz had the Spirit from its birth. Gospel music is in its genes”); the importance to him of the birth of his daughter, Luiza (“The baby is the big thing … a new outlook; everything that came before was valuable training for what will come next”); having faith in himself (“It just doesn’t hurt like it did before … I used to be revved up, having something to prove … Now, it’s more like I believe in what I do”); and the ability to think “big”–being involved in projects such as the splendid Fred Hersch settings for Walt Whitman’s Leaves of Grass, a concert with Orbert Davis’ Chicago Jazz Philharmonic, and his 2010 Grammy Award winning Coltrane/Johnny Hartman tribute Dedicated to You CD.

I first heard Kurt Elling “live” at the Monterey Jazz Festival in 2003. I was present, backstage, when he finished a set in Dizzy’s Den. He was nattily dressed (very hip threads or dry goods!), and carting “a ton of attitude” (as someone else has written). He even seemed pissed off when he came off stage (over something that had gone wrong during the set? The sort of thing perfectionist performers are aware of, not the audience?), or else he was just pumped, like a boxer who’s won a unanimous decision after fifteen rounds of work. I thought, “Hmmm, another Sinatra? Right down to temperament?” Kurt himself has commented on this influence: “People think of me as outre, bizarre. Yet Frank is one of the guys that I spent a lot of time checking out and learning from.”

Elling can be intense, but the next time I got near him was at an IAJE conference in Long Beach, and my Jazz Journalists Association buddies Dan Ouellette and Stu Brinin and I ended up drinking with not just Kurt, but Kitty Margolis (and her husband Monty), Karrin Allyson, Jenna Maminna and Nancy King. I thought, “Wow, I’m sitting here drinking with five of the finest jazz vocalists in the universe at large, at least as we know it!” In this setting, Kurt was decidedly relaxed.

The next time I saw him was when he served as Artist-in-Residence at the Monterey Jazz Festival in 2006. He gave a performance at an intimate downtown venue called Monterey Live, and my wife Betty and I sat just a few feet away from him as he sang: the setting reminding me of small clubs I used to play piano in myself in New York in the mid-Fifties: cozy and compatible. After the show, I had a short conversation with him. He was open, cordial, witty—a “good guy,” accessible (a thing sometimes rare in top performers). In 2008, Kurt showed up at our MJF Sunday Jazz Journalists Association brunch, walked right up, jauntily, and said, “I’m hobnobbing with the fourth estate.”

One more note on Kurt Elling’s range before I turn attention back to Beat Generation “roots” or influence. The “Beats” were not often noted for this (Rexroth’s unintentional comic severely serious “Thou Shalt Not Kill”; in another poem, he writes, “I take/myself too seriously”), but Elling has a sense of humor. One of the finest (funest) moments of the 2008 Monterey Jazz Festival, I felt, came when singer Jamie Cullum joined Kurt on stage in Dizzy’s Den, for one of the Festival’s last (Sunday night) sets. I was sitting stageside, in the dark, back against the wall, enjoying Kurt, Ernie Watts, and the Laurence Hobgood Trio, when a very small person (who would turn out to have a large voice and huge heart) sat down next to me. When Elling sang “Say It (Over and Over Again),” this person began to sing to himself, softly but slightly off pitch, so I wasn’t sure it was Cullum, even though I’d heard a rumor that he might appear. It was Jamie Cullum, however, and next thing I knew he was up on stage, very much on pitch, and the two vocalists exchanged classic playful banter—much of it related to “size.” When Cullum spoke of a woman claiming someone was “tall, dark, and handsome,” Kurt said, “I don’t believe she was talking of you.”

Jamie Cullum: “I have a very high opinion of myself.”

Kurt Elling: “That’s not something visible to the naked eye.”

Cullum: “Small things come with big packages.”

It was a joyous, earthy exchange, filled with respect, with camaraderie. When I left, Cullum was standing alone backstage and I said, “You two guys were great!” He smiled and said, “Thanks.”

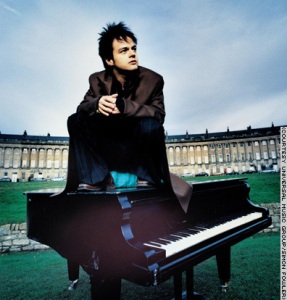

Here are Jamie Cullum (leisurely sitting on top of a piano!) and Kurt Elling at work alone—a great “team” when they got together at the Monterey Jazz Festival in 2006. (Photo credits: http://www.fanpop.com and http://www.criticsatlarge.ca)

Up until the time my wife Betty and I arrived in “The City” in 1958, the only “literature” I’d read regarding jazz was either liner notes on LPs or largely academic works such as Barry Ulanov’s A History of Jazz in America. I dug Mezz Mezzrow’s loose Really the Blues (with its glossary so you could translate the hip talk: “Well tell a green man somethin’, Jack. I know they’re briny ‘cause they dug me with a brace of browns the other fish-black, coppin’ a squat in my boy’s rubber, and we sold out. They been raisin’ sand ever since.”), but it was difficult to rely upon Really the Blues as “history.” What Mezzrow provided was legend or myth. Robert Graves defined mythology as “the study of whatever religious or heroic legends are so foreign to a student’s experience that he cannot believe them to be true,” and it was hard to believe Mezz Mezzrow.

Not long after we’d settled in San Francisco, on my first visit to City Lights (the universal navel of North Beach, along with Vesuvio bar, next door), I saw Allen Ginsburg, Peter Orlovsky, and I believe it was Gary Snyder emerge and hop in their O-honest-to-God Volkswagon bus and take off for—where? The Sierras, I like to think. In the bookstore that day, in the basement, I discovered the Evergreen Review “San Francisco Scene” issue—and bought it for $1.00. It featured an open letter (and a poem) by Kenneth Rexroth, Lawrence Ferlinghetti’s “Dog” (which Bob Dorough would make fine music of: the first piece combining jazz and poetry that, to my mind, really worked well—too often, otherwise, the practitioners of these two separate “genres” just didn’t seem to be truly listening to one another!), Henry Miller’s “Big Sur and the Good Life,” Jack Kerouac’s “October in the Railroad Earth,” Allen Ginsberg’s “Howl,” and poems by Brother Antoninus, Michael McClure, Gary Snyder, Phillip Whalen, and Jack Spicer.

What really threw me for a loop was reading Ralph J. Gleason describing the San Francisco jazz scene. Here, at last, was writing that matched the music—was truly worthy of it, was as vital and engaging as jazz itself! The piece began: “San Francisco has always been a good-time town. For periods it has been a wide-open town. And no matter how tight they close the lid and no matter the 2 A.M. closing mandatory in California, it is still a pretty wide-open town …A high-price call girl, flush from the Republican convention and an automobile dealers conclave and happily looking forward to the influx of 20,000 doctors, 8,000 furniture dealers and divers other convention delegates, put it simply. ‘San Francisco is the town where everyone comes to ball, baby,’ she said … This spirit of abandon goes hand in hand with a liking for jazz, because jazz is, no matter how serious you get about it, romantic music by and for romantics. What could be a better place for it to flourish than a town where everybody comes to ball, baby?”

Wow! You could DO that?! You could write that freely, that openly, that wildly, that intimately, personally, that much like jazz itself when writing about this serious art form—what some writers would later call (not all that accurately perhaps; Charles Ives, Samuel Barber, and William Grant Still, yes, but jazz in and of itself?) “America’s Classical Music”? I was thrilled by what Gleason was doing—his overall approach. I’m not sure enthusiasts, ardent “fans” but non-musicians such as Allen Ginsburg and Jack Kerouac understood the full nature of jazz, its complexity and demands beyond “freedom,” but they liked the stuff well enough and formed aesthetic theories regarding “spontaneous bop prosody” which they applied to their own work. In his Roads to Quoz: An American Mosey, William Least Heat Moon (a fine writer himself), says, “I was eighteen when On the Road came out,” and he goes on to mention Beat literature as work “my teachers considered worthless it not trash.” Remember Truman Capote saying, “That’s not writing, that’s typing”? Moon wrote, “To the teenage brain, of course, there is no higher commendation,” but goes on to say that his “sense of language was then too innocent and uninformed … to see the undigested ideas and hurried assemblage in so much Beat writing,” and if he did see “an occasional solecism (rife in Kerouac’s novels), I defended it as proof of spontaneous creation—a howling artistic challenge to the rigidities and conformities dulling the ‘50s.”

Here is a photo of jazz columnist Ralph J. Gleason–and a copy of the special San Francisco scene issue of Evergreen Review ($1!), which I still have (Photo credit: http://www.retrovideo.com)

Which Beat writing was. I recall what now seems a somewhat ridiculous Civil War going on between “closed form” and “open form,” “cooked” and “uncooked,” “clothed” and “naked,” “traditional” and “post-modern,” “establishment” and “underground,” “academic” and “free,” “formalistic” and “organic,” “inherited” and “forward-looking” poetry. Moon adds, “I would argue half-heartedly that the Beats were important for what they said rather than how they said it”—but he divests readers of the illusion that Kerouac spent a mere nineteen days painting words, a la Jackson Pollack, on his endless roll of “Teletype”: “If only we’d known the truth: Kerouac worked at the book for more than a decade and executed several drafts of On the Road, both short ones and long, including a version in French. The more notorious Kerouac’s four manuscript scrolls became, the more fables about them increased.”

In this manner, perhaps, the legends of “angel headed hipsters” are born.

At the time of the 2009 Monterey Jazz Festival, I finally had an opportunity to sit down with Kurt Elling and discuss his Beat “roots.” We first chatted about Beat Generation writers over breakfast at the Hyatt hotel, and then went outside for a forty-five minute interview. Inside, we had been talking about Kenneth Rexroth, the Beat Generation “paterfamilias” whose poetry had such an influence on both Kurt and myself—so we started in again there:

Kurt Elling: “You mentioned the breadth of his interests and his abilities, such as teaching himself to be able to translate Japanese. We talked a bit about his awareness of the destruction that human beings at that time were waging on the earth, and his reverence and his humility before nature comes through in so many of his poems. It’s striking to me how successfully and organically he was able–in the same poem–to refer to the splendors of the earth and refer to the quick passage of time, and how small we are in comparison to the earth, and a sense of reverence and romance: real romance, the romance of sentient beings and not just people walking around who are brain dead, but real sentient beings. That’s what makes his poems diamonds. It’s because there’s so much refraction of light and intelligence and desire all compacted.”

Me: “It’s amazing, and not an easy thing to do.”

Kurt: “Yeah! I have real respect for his abilities. It’s the kind of thing that I strive for, to even be aware of walking around, let alone to have the kind of poetic gifts to be able to articulate them to other people in such a way that would be meaningful.”

I mentioned a 2002 Cadence magazine interview in which, referring to Beat Generation writers, Kurt had spoken of their “dark side,” and the paradox that they were “some pretty self-satisfied, self-righteous cats, who were trying to tell everybody what to do, in their attempt to have everybody stop telling them what to do.” “I loved that,” I said, and he laughed. I then asked how, born in 1967 as he was, he’d ever got into what the Cadence interviewer called “Beat texts.”

Kurt: “You know it’s tough to trace an exact lineage. I know that hearing Mark Murphy’s records, when he did the ‘Bop for Kerouac’ and he did the readings, those were very special records and I know that that pointed me to actually picking up the books if I hadn’t yet. Maybe a better way of saying it is: it gave me access to the books. And once you start down the path, then if you find something captivating, you want to encompass as much of it as you can. So that intent grew pretty naturally, and not only from an intellectual concern or curiosity, but also because some of the things that Kerouac and Ginsberg were going after, I have a strong … well, Kerouac opens my heart a little bit because he’s so … he’s just so sincere.”

Me: “In the Cadence interview, you said that the part that interested you the most was ‘the transcendental aspect … the yearning for the eternal’ and ‘the love that he had for people.’”

Kurt: “Yeah, he’s so vulnerable, he’s so sincere, he’s trying so hard and he’s such a goof. He’s so fragile, yet at the same time he’s really reaching out to what it means to be alive while he’s alive, and to glorify through his work as a writer just his life, his experiences and his friends’: the trials and tribulations and the victories of just being alive in that moment, in that era. And it’s his sincerity and his earnestness that was his greatest strength, but it was also his greatest vulnerability. I’m sure it’s what put him in the ground. Ideally what you have is an ego that has a flexible protective armor and when you write and when you consider and when you love, there is no armor and you are completely open and your consciousness receives and speaks with perfect unguarded honesty, but the world is an unforgiving place, and for somebody who can’t get their armor up when you need armor, you’re going to get crushed beneath the wheel, and it certainly came to him in a way–you know, fame–everything that went down. It seems to me he was never the kind of character that had any desire whatsoever to thrive in that public environment. He had desire, but it was the desire of a child who didn’t know he was playing with fire, so …”

Here is Jack Kerouac, alongside Kurt Elling—each providing the world a similar look; each with his own “flexible protective amor.” (Photo credits: www.gq.com and http://www.bluenote.com)

I mentioned that my wife Betty and I had lived in Greece for a year and I was astounded when I heard university students coming home from the discos at night, singing “pop” songs composed by the great composer Mikis Theodarakis, with lyrics by Nobel Prize in Literature recipients Georgos Seferis and Odysseus Elitis, and I thought, This could never happen in America: this blend of outstanding music and first-rate poetry, not just standard song lyrics. “But you’re making that happen,” I said to Kurt, and asked about the risk involved.

Kurt: “It didn’t seem risky to me. It just seemed … What’s the right entrance for this? The possibility inherent in communicating as a singer, as a speaker in the jazz milieu is very broad at the outset: the number of avenues that you have just because you’re a singer and you speak in language and you sing with language. You can sing a standard, you can swing a standard, you can rearrange a standard, you can juxtapose a standard with another standard, you can scat—that’s just the baseline; but if one has studied the history of jazz singers: there’s Mark Murphy and his spoken word stuff; Sheila Jordan, the way she’s gone about things; Jon Hendricks and the way he makes a presentation and is so erudite and tells all these marvelous stories; Betty Carter and the intense and far-reaching scope of her just straight up musicianship and improvisational ability—and then like me, if you’re not just interested in the music, if you’re interested in an entire root system of the jazz culture we have, much of which grows out of the 1950s and 60s and the time that you are obviously more hugely familiar with … it’s impossible for me to have lived in that era, but because part of my job is to read, mark, learn and inwardly digest the history of the sound, and because the influence of the poets and the painters and the sculptors and the politicians and the arguments of the times were so much of a piece with the way the musicians were playing and gave them a spur to keep exploring, to find new ways—‘Oh, we’re going to the moon,’ or ‘Oh, we’re in danger; Cuba’s got missiles,’ whatever it was—the fears and the energies and the aspirations of the urban life of America at that time was so tumultuous and trembling and expanding and obliterating the past and re-creating it, and that’s all in the best parts of the music that jazz was responding to and jazz was commanding, leading the way, hearing before the people heard how tumultuous it was going to be and playing it and shocking them with the news … I’ve been given a peculiar set of gifts. I’ve been given a voice that resonates and can move people. And I’ve got an intellect that’s interested in things beyond just the music. And I’ve been given opportunities to learn from some intensely intellectually very gifted people and to cop what I can cop, to understand what I can understand, and to know that there is a glorious possibility in every moment. If I was just quiet enough and writer enough every breath is a poem and every situation you are in–painful, beautiful, ugly–it’s just all poetry, all the time. You just have to be available to it.”

Me: “Somewhere else you talked about ‘the daily discipline that it takes to see the world with fresh eyes and to try to apprehend everything that’s coming to you as a potential gift: there’s poetry in that.’”

Kurt: “Yeah, so the [Beat Generation] books moved me, the books informed me, yet it was not just out of a kind of intellectual curiosity. It’s because I really want to know. My questions are the ultimate questions. There’s a reason I was in graduate school for three years, reading Haberman and Schleiermacher.”

Of the latter, theologian Friedrich Schleiermacher, Mark Schorer (in William Blake: The Politics of Vision) has written that poet Blake “argued like Schleiermacher that religious intuition lifted the believer into a higher sphere, provided him with an enriched perception of the wholeness of experience,” and provided “an aesthetic experience of harmony that is potential in the world … a truly imaginative moral act, in which selfish isolation of human needs is transcended in the sense of a larger unity and a nobler universe”—all of which fits into Kurt Elling’s own aesthetics and sense of purpose very well.

Me: “I was going to ask you about the possible influence of your church background. The psalms. The love of language. The love of those sounds.”

Kurt: “A love of language, a love of sounds—an understanding of the emotional impact that a ritual environment can bring, and the importance that music plays in that ritual environment. That ritual environment has definitely informed the way that I approach a given concert. I want to take people right out of their seats right from jump if I can and alert them that something is going to happen to them beyond ‘Take the “A” Train.’ Then I try to take them there, or go with them, whatever the right way to say it is. And I think this is part of the task, the calling that I’ve been given. This is who I am. These are the roots I come from. I guess my first experience of music at all was in a theological environment: music in the service of the emotional and spiritual growth of a group of people—and that’s not something that I have any desire to leave behind, just because I’m in a different genre now. But I’m not the only one. There’s a whole history of jazz musicians: Brubeck has written sacred concerts, Ellington has written sacred concerts, Mingus was no stranger to spiritual aspiration; Trane obviously, Art Blakey—Why did he call his band the Jazz Messengers? Right? I’m OK with fitting into that tradition as well. I try not to speak this explicitly about it, or I don’t speak this explicitly when I’m on the stage. And I usually don’t even speak about it this explicitly when I’m specifically being asked about it. I don’t want to lead with that. I want to lead with the music, lead with the joy, lead with the swinging experience, lead with the kick, and then when everybody’s relaxed and happy and they’re grooving, then you’ve already done 90% of your work; and then any specific message … only it isn’t a specific message other than something I think Kerouac would have identified with: we’re here, and it’s not about money or winning … it’s just about souls having a good time.”

Me: “The Japanese call it ‘kono-mama,’ or suchness—living the moment, the here and now.”

Kurt: “Yeah!”

Two more album covers: Flirting with Twilight and Nightmoves.

Me: “In the liner notes to your The Messenger CD, you said, ‘I am not “The Messenger,”’ but writer Neil Tesser added that your union of words and music ‘creates something provocative and yet serene; it leaves no doubt that the singer has quite a bit on his mind.’ He said your message ‘grows from the intersection of jazz and poetry, the place where the beat meets the Beats.’ You’ve also said, with regard to Kenneth Rexroth’s poems about impermanence: ‘love-time is brief.’ Is that the message, if there is one?”

Kurt: “You know it’s tough for me, because I do feel like I have a mission or a calling. I feel like I’m doing the thing that I’m here to do. But I don’t feel comfortable and never really have … I don’t have a specific theological agenda, other than peacefulness and joy. There’s a reason I’m not an actual priest. I don’t want to prescribe how it’s supposed to go for people. I just want to help them remember what it feels like sometimes.”

Me: “’I learn by going where I have to go’” [a line from Theodore Roethke’s poem ‘The Waking,’ which Kurt Elling recites/sings to Rob Amster’s bass accompaniment on his Nightmoves CD]

Kurt: “Yeah, I just want to help them remember what it feels like to be at peace and to be happy. One of the psychological definitions of happiness is self-forgetting, where you are no longer aware of yourself, because every time you are aware of yourself, then you have desire. Every time you are aware of yourself you have ‘Oh, my back hurts’ or ‘I’ve got to do this job.’ Or ‘What’s on TV?’ or ‘I want to buy that.’ Or ‘I’m hungry’ or ‘Look at that girl’—or whatever. And the times when we are actually at peace and are happy, we’re not thinking about any of those things. We’ve been able to let all of those thoughts go and to simply be. Which is a Zen moment. It’s satori. [enlightenment] Music is one of the primary ways that regular people experience this, without even knowing it. The music starts and they listen, and if the music connects with them, and if the performance is emotionally resonant, then for ninety minutes, they forget themselves and they are totally in the moment. They are experiencing a period of time in which they have no concerns, no doubts, no worries, no fears, no desires other than to continue having this experience. So that’s why I say there isn’t really a message. A message? It’s the experience that you are providing for people and then, if in the course of that I can take them to a place where they’re like, ‘Wow, what’s he singing? Huh!’ But I don’t want to take them any further than that, because then they start to follow their thoughts again. If I structure my set the right way, they’d follow my thoughts. And I’ll divert them through any experience that, at the end, they have joy and they have light and they’re happy that we were there—and then they want to come back for more. And then, from a French sense, if I’m really doing my job, then the surest proof that I’m a real artist is that, when the show is over, they all go out and have drinks together and have conversations that last into the night. That would be great!”

We left off talking about “the Message” in his music (or the music as message enough in itself) and continued talking about the difference between what Kurt had at one time called his “rants” and his “monologs” or pieces consciously composed or prepared, “worked out in advance.” I’d found a quote in the liner notes to his The Messenger CD in which he said he found the former, the “rants,” more “rewarding.” Still true?

Kurt Elling: “Well, I’m married now. [laughs, openly] Ranting is something a monk can do. Again, you really have to have enough solitude for these things to gestate, and to have enough of a solid kernel of something so that when you begin it explodes and you don’t know where it’s going to go. So the carefully constructed things tend to be something that I do more often now. But I’m still, with Mark Murphy or Sheila Jordan or getting with Von Freeman, any of these teacher figures of mine … they can kick me back into that space pretty quickly, if they just give me a look, and hook, and then I’ve got to be like, ‘OK, gantlet’s down, let’s go.’”

Me: “The challenge is on. I found a review of a concert you gave in Michigan, and a reviewer for the Kalamazoo Gazette wrote that you were ‘thoroughly hip and groovy, this reincarnated poet from the Beat Generation—he said “man” and “cat” a lot and spoke with a great many flowery witticisms.’ The reviewer also said you ‘charmed the audience, which included several people celebrating Mother’s Day.’ But the slang term ‘Beat’ goes all the way back to 1860 and the Civil War, and the notion of hipness (I was “raised” on Slim Gaillard’s “voutie oroony” and Mezz Mezzrow’s book Really the Blues) had been around for some time before the Beat Generation. How do you feel about being type cast as ‘thoroughly hip and groovy’”?

Kurt: “It’s par for the course. They’re going to write about what they’ve going to write about. Spice that people don’t think exists anymore, or that it’s just in books or people’s memories—or even the guys that lived it don’t talk like that anymore.”

I mentioned young MFA in creative writing candidates I met at a writers conference in Gettysburg who, when I talked about living in San Francisco in 1958, said, “You were a Beatnik! To us that was the Golden Age!”—even when I said I was not fully aware, at the time, that I was a “Beatnik,” and that we were dirt poor to boot and it was no “Golden Age.”

Kurt: “Yeah, it’s all the Golden Age, and none of it’s the Golden Age. You know, frankly, musicians on the jazz scene in Chicago, certainly the people I was hanging out with, well, I gravitated toward the older musicians because I wanted jazz father figures, and I wanted to have their blessing and their encouragement and their love and their acceptance. I wanted to touch the past through them, and that’s how they talk! [laughs] So I wanted to be like them. It’s a little bit like what Gary Grant said: he became Cary Grant by pretending to be him long enough so that he did! He became him! So, now it’s just part of the thing, and I think it’s cool. It’s become an organic part of me, and even here at the Festival, I’m not the only one, man. Talk to Joe Lovano for a couple of minutes. Some of us just want to be a part of that. We want to continue to manifest that energy, because it’s good to be a slick, you know? It’s chic! It’s not ordinary.”

I quoted another portion of Mezz Mezzrow’s Really the Blues, previously mentioned, for which Mezzrow even provides a glossary, and a translation, at the back of his book: “All I got left is a roach no longer than a pretty chick’s memory. I’m gonna breeze to my personal snatchpad and switch my dry goods while they’re [his lady friend is plural!] out on the turf,” etc. I told Kurt that, as I kid, these words became embedded in my head (and are still there, indelible), even before I learned the opening lines of the Declaration of Independence.

Kurt: [laughing] “There you go!”

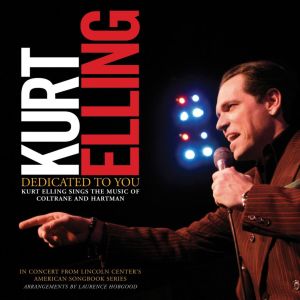

Here is the cover of Mezz Mezzrow’s Really the Blues, a book that became my jazz “Bible” at age fourteen (a book, often consulted, well-worn) I still possess–and Kurt Elling paying homage to John Coltrane and Johnny Hartman in Dedicated to You.

Me: “Let’s talk about diversified experience or what you’ve described as ‘multi-disciplinary art events,’ full-blown performance pieces that encompass poetry, spoken word, dance and theater. I’ve been fascinated by the possibility of that sort of thing for a long time, and you’ve done so handsomely with it. An Italian reviewer praised you as ‘immensely versatile,’ commenting on the fact that you ‘keep changing from one moment to the next’—charming audiences with a traditional ballad, then scat-singing, ‘commanding [your] voice as an instrument, acting while singing,’ etc. Yet I grew up in an era of ‘specialization,’ when, if you tried to do many things, people thought you probably did not do any one of them very well. I had a year when I ended up in an anthology of best American short stories (with Raymond Carver and Joyce Carol Oates), was exhibiting woodcut prints in the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts and Smithsonian Institution, and was playing keyboards with a folk-rock group called the Salty Dogs. But I had to fight to convince people that all of this ‘stuff’ was coming from one source: my own soul! I was also teaching at a state university in Wisconsin and when the question of tenure came up, my chairperson called me into his office and, looking straight into my eyes, asked, ‘Bill, what is it you really do?’ That was the thinking of the time, the era, but today, things have changed, and ‘multi-tasking’ seems to be in.”

Kurt: “Well, again, if as an individual artist you could do anything from ranting to soliloquy to vocalese to straight up extemporaneous communication, I think that one already probably has a natural consciousness that is syncretic, one that wants to pull things together and see how they combine. The most interesting thing is not to try to combine everything with everything; it’s to combine this interesting thing with this very disparate interesting thing, and to have a new viewpoint on everything else because you never would have thought of those two things together. So when the commissions started, who am I to say no? I gave it my best shot. They were always on a shoestring budget and they were only meant to run one or two nights at a time, but I’d give it my best shot because it was just a great creative challenge to try to figure out how these things would work together. I’m really proud of the results. I feel like I have a good organic sense of the way that dance and music and spoken word would go together, especially if I’m familiar enough with the choreographer’s work. Because a lot of times, if I’m seeing someone who has a great choreographic gift, and insight, that often inspires stories in me, so I’m adapting my thing to something that goes with this. It’s that kind of call and response, if you will.”

Me: “Is the ‘Encounter Without Prejudice: An Open Tribute to Allen Ginsberg’ project on film?”

Kurt: “No, it’s not really on film. There are audio recordings of it, and I’m actually having to have friends of mine back in Chicago dig through the Steppenwolf Theatre archives and the radio archives because it was pre-digital and just never had the budget … well, it’s not like ‘let’s set up two digital cameras and have done with it.’ The reason I’m having to go through and get that stuff happening now anyway is that I’m applying for a grant for a new piece and they all want proof that you’ve actually done the things that you’ve said you are capable of doing.”

Me: “Can you talk about the new piece, or does discussing it beforehand jinx it?”

Kurt: “I’ve had an idea that for a few years has been gestating. It will be somewhat autobiographical, but it will also be based on Joe E. Lewis and The Jokers Wild: just using that as a very basic skeleton, but doing it in a very contemporary context and in that way sort of embracing history, because I have all these deep parallel experiences to Joe E. Lewis. The Green Mill was the club he was working in when they [mobsters] cut his throat. I know the tunnels. I know the ghosts of that place, and that it’s still a functioning club and it still has all this energy and it’s living. I’m not that interested in the old-time gangster thing. That seems real corny to me, and I want to present contemporary music as a heavy part of this, so we’re talking about a contemporary setting of an artistic tragedy—one that features a live and semi-spontaneous score.”

Me: “Will it work that way: as a legit ‘Greek’ tragedy, hubris, denouement and all?”

Kurt: “I’m working on the form. I’m not sure how its going to end, whether he pulls himself out or what the thing is, but I’m sure you can well imagine what an intensely mental game … well, I don’t know if ‘mental game’ is the right way to put it, but it’s something for me to contemplate: his life and the lives of people who have an artistic gift in a very special frequency and for whatever reason have that gift taken away from them. And then, what do you do with the rest of your time? If you can’t have your work in the Smithsonian and play music … if you don’t have a diversity where you’ve got back up things—then what?”

Me: “When people ask me if I ever get ‘writer’s block,’ I say,’No, I just go someplace else,’ which is a fortunate option I think.”

Kurt: “Yeah! I think this kind of idea goes to not only the questions that would specifically haunt us, but questions of regeneration, questions of self. The choice of one’s identity, and the creation of identity. I want to say that’s an American thing. It’s not just that of an individual artist. This is not just a genre-wide phenomenon. Here are all these musicians who are creating themselves by creating music. They’ve done discipline, they’ve learned history; they’ve learned about music and now they are declaring themselves. And that’s an American thing.”

Me: “Any last thoughts? Twenty-five words or less?”

Kurt: “Power to the people!”

Me: “Thanks for your time.”

Kurt: “Oh man, it’s nice. It’s nice to have a conversation about this stuff. And I appreciate your welcoming my efforts from my generation to connect.”

Here’s Kurt Elling making another essential connection–with an audience as he lodges lyrics in their minds and hearts forever. (Photo credit: http://www.the guardian.com)

In a recent JazzTimes column, writer Nate Chinen states that, because of Kurt Elling, “the state of jazz singing will be different in the coming decade than it was when he arrived, and I dare say it will be better.” As evidence, he quotes David Thorne Scott, an associate professor in the voice department at Berklee College of Music, who claims, “Among my jazz students, [Elling] is the contemporary singer that I have cited the most as an influence. I always expect it from my guys, but it’s the women too.” And Dominique Eide, “an accomplished jazz singer and revered faculty member at the New England Conservatory,” adds, “Technically he’s so impressive, and I think students feel the weight of musicianship behind what he does, in his transcription and his writing of lyrics to other people’s solos.”

I’ll mention two impressive “techniques” that Elling employs when singing ballads—approaches that, I feel, owe something to the Beat Generation legacy of risk-taking and “artistic challenge.” The first is a relatively “straight” or straightforward, respectful (in terms of tradition or what has gone before) approach, but one to which he brings or lends his own unique—personal, original–sense of tempo and phrasing. He not only enhances, but transforms and transcends what we have become accustomed to hear, or are familiar with, within the standard ballad repertoire. A Russian literary theory called ostranenie, or “defamiliarization”–a theory much in line with the Beat Generation’s own aesthetics–was based on an incident in which Leo Tolstoy once spent twenty minutes dusting his room without having a single thought in his head. For Tolstoy, that was a crime. He was embarrassed: caught with the trousers of his consciousness down, so to speak, and equated the state to not existing, being dead. Critic Viktor Shklovsky picked up on this incident and described ostranenie as destroying the habitual logic of associations, a deliberate cultivation of the unexpected—the world of everyday reality becoming more perceptible in the process, objects restored from mere “recognition” to actual “seeing.” Or hearing. Of all the contemporary musical artists I know, Kurt Elling may come closest to putting “defamiliarization” into practice.

On his fourth CD, Flirting with Twilight (2001), and again on Dedicated to You, Kurt severely alters the customary tempo of “Say It (Over and Over Again).” He slows it down to a near halt (talk about “risk”!). There’s ritardando in music of course (holding back, gradually diminishing the speed), but when I tried to sing “Say It” at Kurt’s tempo, I just sounded mentally retarded, or aphasic. Kurt handles the tempo beautifully—as if he were swimming and singing, underwater. His slow motion phrasing gives you the eerie impression that time may well have swung to a halt, but the effect matches the special pleading (“never stop saying you’re mine”) perfectly—and not just pleading but praying this might be so. The slow motion approach, taking the tempo down to a near standstill, also occurs in “Every Time We Say Goodbye” (on his 1998 This Time It’s Love CD), and–as with “Say It”–it fits the song’s content just right. The existential dilemma—“Why the gods above me, who must be in the know, think so little of me … they’d allow you to go”—gets lodged in the mind and heart forever.

A second approach is strict vocalese, or what Dominique Eide described as Kurt’s “transcription and his writing of lyrics to other people’s solos.” On “A New Body and Soul” (Nightmoves, 2007), the content embodied in Dexter Gordon’s improvisation, the original melody with its emphasis on a heart that’s “sad and lonely” and stuck fast in a supplicating state is there at the start, but the emphasis is shifted to a head that’s “inept,” not a heart. Kurt’s own lyrics are loaded with “free” Beat Generation talk, or his “rant” phase (generous, expansive, meandering, here, to the point, perhaps, of overkill). The talk includes everything from allusions to “fear,” Orpheus, “the itsy-bitsy spider,” and a “cosmic freak show” that consumes mind, body, soul, and heart.

My favorite “vacalese” piece is “Freddie’s Yen for Jen” (on This Time It’s Love), which starts out with succinct lyrics worthy of Kenneth Rexroth:

“Love is wild in her; / I confuse her love with the sea. / She is a rare fantasy told to me …”

The single syllable word “rare” somehow ends up sounding like “mir-a-cle”—but the subtle effects erupt, the slow tempo changing to one that’s decidedly “up.”

“”But her kisses. / I dig her kisses / while washing the dishes / or feeding the fishes …

The loud Bob Dylanesque rhymes produce the effect of mockery or doggerel, and from that point on, it’s anything goes—and it does. The “poetry“ gets kinky, playing heavily on the “k” sound: “Kick-it, kig-it, kig-it kisses/kisses that will make you holler love/and that you’re glad enough to be a man!” In a wild middle “talk” section, his “chick” is flying all around him, with “a wiggle that will make a clock stop.” They “tether together,” the word play wide open, now, like the love, but not quite as indulgent as in “A New Body and Soul” (aside perhaps from those “chewy kisses”). It all converts to a grueling instrumental scat and ends on the word—guess what?—“kiss,” of course.

With regard to a fully successful “marriage” or union of words and jazz in Kurt Elling’s work, it might seem fair to ask the same question I did the first time I heard Kenneth Rexroth read to music, “But is it poetry?” I do feel we’ve come some distance since Rexroth’s “groundbreaking” efforts or what William Least Heat Moon recognized as “undigested ideas and hurried assemblage,” and I feel that Kurt Elling has found a more intigrated means to combine highly original use of language with jazz in a way that is so thorough, so complete it’s not possible to appraise the words alone as “good poetry” or the music alone as “good music.” The two become one, as they should, and that is the basis on which we might say the work itself is “good” or “bad.” By this standard, what Kurt Elling does is very “good” indeed. For much of his audience, when Kurt sings, the words of a song–even those of the most familiar “standard”–finally come fully alive and mean something, and that would appear to be in the nature of poetry, if not the essence of poetry itself.

My favorite poet associated with the Beat Generation (although he did not like being “fixed” in that way) was Jack Spicer. I first found his brilliant Billy the Kid, the original Stinson Beach Enkidu Surrougate edition, in City Lights Bookstore, but at the time I could not afford whatever it cost (probably no more than a couple of dollars), and I still kick myself for having been a part of that Beatnik “Golden Era.” Spicer described poetry as both a “dance” and a “game”—but the game is a ball game in which you “play for more than your life.” The poet does not become a “master of words,” but is mastered by them; and the relation between reader and writer is “an amorous play for keeps. No tourists allowed.” The committed stance and high standards remind me of much that Kurt Elling said in our interview. A friend of Spicer’s, during a lecture that Jack gave, came up with a host of musical analogies he felt fit Spicer’s poetry. One compared the writer to a jazz musician improvising on a single tune so often that “he has patterns in his fingers and these patterns are so firmly in his fingers that he can allow them to take their own head and do what they want to.” Spicer responded, “I agree with that. But at the same time, you get the kind of thing which you’ve had in jazz since Parker died, with the exception of Monk, where at least I am not moved any more, where you are just showing what you can do with the things which are in your fingers or in your mouth or where the thing is … cool jazz becomes cold jazz.”

Here are Jack Spicer and Kurt Elling—each “mastered by words”—an “amorous play for keeps. No tourists allowed.” (Photo credits: mypoeticside.com and Wikipedia)

While I certainly do not agree at all with Spicer’s appraisal of the state of jazz in general since Charlie Parker and Thelonious Monk, the point is well taken–and has been repeated often–that in any art form, there’s got to be more than technique for the sake of technique. And I would never accuse Kurt Elling of ever going “cold,” of mere finger (or “lip”) exercises. The “weight of his musicianship” may now seem nearly effortless, compatible, truly “cool,” but it has deep roots—not just in his fondness for and indebtedness to the Beat Generation, but in all the hard work and study he’s put in. He’s “learned history”; he’s “done discipline.”

Kurt Elling, in writer Nate Chinen’s estimate (“Let’s come right out and say it”) “is the most influential jazz vocalist of our time.” Kurt’s legacy may well prove to be the extraordinary manner in which he has combined the art form of jazz with his own strong sense of language, its imaginative power and its wealth of meaning. He is certainly one of the most original, most unique vocalists to explore that relationship.

When, back in 2010, I assembled the five pieces I wrote for my JazzWest blog, I immodestly felt I must have written THE definitive “study” of Kurt Elling’s music. I don’t know that he ever saw those pieces, so I don’t know what his opinion of that opinion might have been. Over the years, I did work to refine my original efforts until I had completed the essay–“Kurt Elling and The Beat Generation”–to satisfaction. And it’s been a pleasure to read the recent JazzTimes and Down Beat articles on him, and realize that Kurt is still going strong, still offering “great melodies” and “express[ing] authentic emotions”—still “the real deal.” I heard Kurt Elling and Branford Marsalis together at the 2016 Monterey Jazz Festival, and they were definitely “the real deal.”

Thank you, Kurt, for all the pleasure you’ve provided by way of your inclusive, and continuous, talent and dedication to jazz—for your everlasting faith in what you do.