My most recent post on Bill’s Blog–“San Francisco State College in 1962–Wright Morris”–was the first in a series of two pieces on my experience as a graduate student in Language Arts (Creative Writing) at the College–“one of the most rewarding periods of my life.” I said the second post would focus on poet Leonard Wolf–another major influence at the time–and see us through the acquisition of my Master of Arts degree in May of 1963. I’d like to offer that second post now.

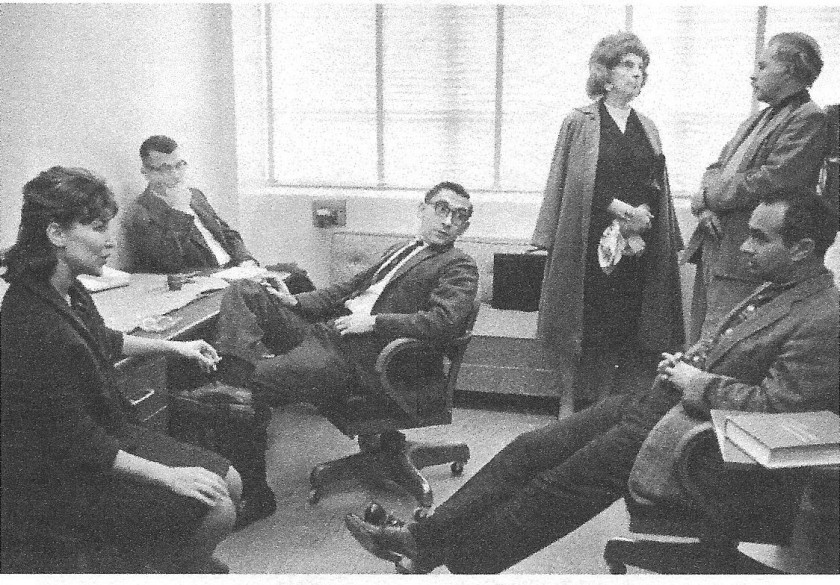

In the first post, I claimed that, in 1962, the Creative Writing faculty consisted of some of the finest writers of the era, one of whom, Wright Morris, I focused on exclusively. Here’s a photo, taken in 1964, of a portion of the staff in the office of Wright Morris, who is standing (far right) talking to Kay Boyle (Death of a Man, Three Short Novels: The Crazy Hunter, The Bridegroom’s Body, Decision, and several short story collections); Leo Litwak seated far right (whom I would come to know well years later, when we were guest writers at the Foothill Writers Conference; Leo was then at work on his memoir, The Medic: Life and Death in the Last Days of World War II), Bill Weigent in the center; Mark Harris far left in the back (Bang the Drum Slowly, The Self-Made Brain Surgeon and Other Stories, Mark the Glove Boy, or The Last Days of Richard Nixon, Diamond – The Baseball Writings of Mark Harris), and Judith Shatnoff down front: (Photo credit: Haunted: The Strange and Profound Art of Wright Morris)

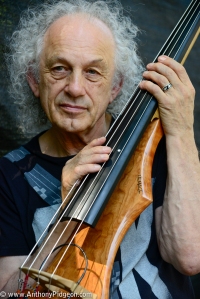

While I’m dropping names (and the names of books), I might as well mention other faculty members of note when I arrived in 1962. Walter Van Tilburg Clark (author of The Ox-Bow Incident and The Track of The Cat) was Division Chairman, and would serve as my primary faculty adviser. Poets James Schevill, Bill Dickey, and Leonard Wolf (much more about him coming up) would make up my Masters of Arts thesis committee—and other writers on the staff were Ray B. West (Rocky Mountain Stories, The Art of Modern Fiction, Kingdom of the Saints); poet/critic Mark Linenthal (who liked to tell students “Everything I learned about poetry, I learned from jazz.”), James Leigh (The Rasmussen Disasters, No Man’s Land, and What Can You Do? Also a jazz trombonist who in 2000 published his memoirs, Heaven on the Side: A Jazz Life); and Herbert Wilner (All the Little Heroes, Dovisch In the Wilderness and Other Stories, Quarterback Speaks To His God).

While I’m dropping names (and the names of books), I might as well mention other faculty members of note when I arrived in 1962. Walter Van Tilburg Clark (author of The Ox-Bow Incident and The Track of The Cat) was Division Chairman, and would serve as my primary faculty adviser. Poets James Schevill, Bill Dickey, and Leonard Wolf (much more about him coming up) would make up my Masters of Arts thesis committee—and other writers on the staff were Ray B. West (Rocky Mountain Stories, The Art of Modern Fiction, Kingdom of the Saints); poet/critic Mark Linenthal (who liked to tell students “Everything I learned about poetry, I learned from jazz.”), James Leigh (The Rasmussen Disasters, No Man’s Land, and What Can You Do? Also a jazz trombonist who in 2000 published his memoirs, Heaven on the Side: A Jazz Life); and Herbert Wilner (All the Little Heroes, Dovisch In the Wilderness and Other Stories, Quarterback Speaks To His God).

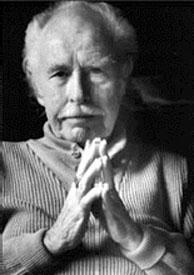

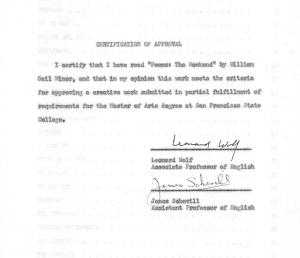

Leonard Wolf, who became my thesis project adviser (my thesis a manuscript book I would call Poems: The Weekend—“A creative work submitted to the faculty of San Francisco State College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Master of Arts”), was–at the time I worked with him–not one of the “well known” writers on the Creative Writing staff, although he had published his work in The New Yorker and other respected journals, along with a book of Poems, Hamadryad Hunted (1948, Bern Porter Press). In 1962, the year I met him, his daughter Naomi was born—and she would become, in the words of Wikipedia, “an American liberal progressive feminist author, journalist, and former political adviser to Al Gore and Bill Clinton,” Naomi Wolf would come to prominence in 1991 as the author of The Beauty Myth. She also wrote The Treehouse: Eccentric Wisdom from My Father on How to Live, Love, and See: a “lovely personal memoir about an unconventional, openhearted man … a wild old visionary poet … passionate eccentric and a radically romantic humanist” who believed the creative force resides “inside all of us.”

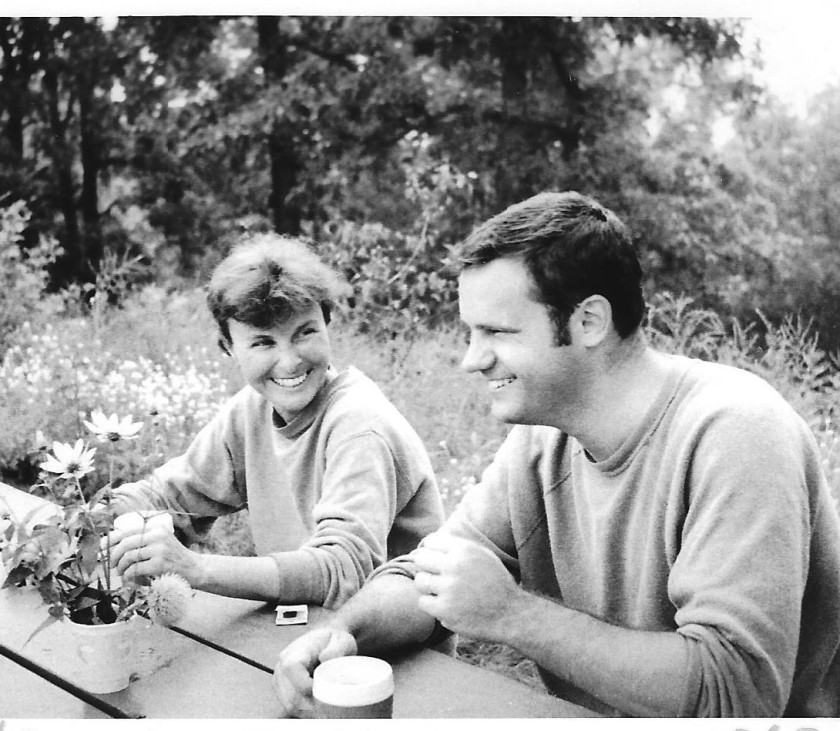

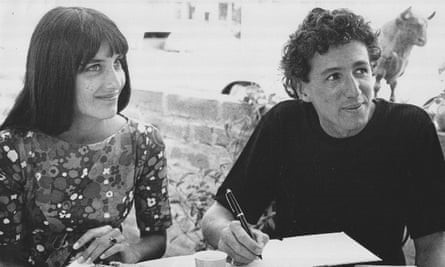

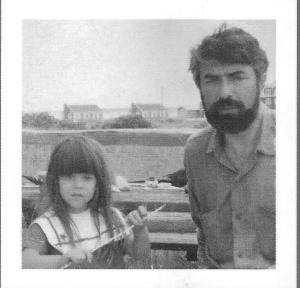

Here is the cover of The Treehouse: Eccentric Wisdom from My Father on How to Live, Love, and See—with father and daughter together in Leonard’s later years; and here is a photo of father and daughter taken in 1966—three years after I graduated from San Francisco State College: (Photo credits: The Treehouse: Eccentric Wisdom from My Father on How to Live, Love, and See)

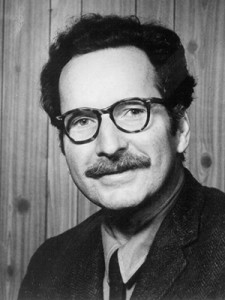

In 1962, I found Leonard Wolf to be a lean, handsome, dark-bearded (he reminded me of photos I’d seen of D.H. Lawrence) purposeful, intense at times, but modest, mild-mannered, accessible, empathic adviser I felt comfortable with the first time I sat down with him in his office. I did not yet know his “history” (which turned out to be nearly as colorful as that of Wright Morris). Leonard Wolf was born in Vulcan, Romania (Transylvania), his name originally ‘Ludovic’, which was changed upon his arrival in the United States in 1930 with his mother, Roseita, older brother, Maxim (Mel) and younger sister, Shirly. After I left San Francisco State College in 1963, Leonard Wolf would, in 1967, start “Happening House, one of many organizations that originated with the hippies of the Haight Ashbury district … conceived as an alternate university, an arts center and a place of learning.” In 1968, he would publish Voices from the Love Generation with Little, Brown—a book I purchased and read while teaching in Wisconsin.

Here’s the cover of that book, and the cover of Leonard Wolf’s book of collected poems, The Stone Cicada, published by Medusa Press in 2001.

I’ve already mentioned (last post) that I had to submit my own work to be accepted in his poetry writing course, and that once he had selected the students he felt qualified, he asked us to meet at his home, rather than in a classroom on campus. I don’t recall exactly, but I think just about ten students would gather there on a weeknight–and all of them talented, interesting people. I was twenty-six, and a definite dowager was in her seventies. She had an elegant home in the Marina section of San Francisco, and we met there on one occasion. I wish, now, I’d kept a list of the students’ names (for future reference—what may have “become of them”), but unfortunately, I didn’t. The sessions held at Leonard’s home were lively, informal, and informative in a multitude of ways (regarding the craft of poetry, and otherwise)—each student respectful of the others, and Leonard open to the needs of each of us.

Aside from the friendship I formed with my sculpture teacher, Cal Albert, at Pratt Institute in Brooklyn in the mid-50s, I’d never been in the “home” of an artist or writer with whom I took a class before, to see what “domestic” life was like for them—so these journeys up the hill above Kezar Stadium to Leonard Wolf’s home were inspiring. His daughter Naomi was not born until 1962, so Leonard’s wife was “carrying” her at this time, and his wife, Deborah, was an interesting, attractive, personable woman. The house was, as Naomi would describe it in her book, The Treehouse: Eccentric Wisdom from My Father on How to Live, Love, and See, as follows (I’ll quote at some length, to give the full effect):

“Our house in San Francisco had been built in 1890, in the style of a hunting lodge. Its foundation, we were always being reassured, was on bedrock. It had survived the 1906 earthquake. Nevertheless, maybe because of the quake, it leaned visibly out of level … I did not live in a room with level floors in it until I was old enough to vote. It was easy, in a house like this, to believe that the imagination was a world that was as normal to inhabit as any other …The house was built so that the entire back end was pitched straight over a cliff. That half perched on two big timbers, with a sheer drop fifty feet down. The cliff-side balconies sagged markedly. Every time you went out on one, you were taking your life in your hands. The front half of the house was buried in wild growth: tangles of nasturtium and ivy covering a steep forest floor, overshadowed by eucalyptus and Monterey pines. When you stood on the roof of the house—which my parents insanely allowed me to do—you could see all the way to the Golden Gate Bridge in one direction, and all the way to the Bay Bridge in the other: a silver necklace and a golden chain binding the city at both harbors … As I curled up with a book in a niche by the ash-laden fireplace, looking out at the evergreens that surrounded the house, continually painted and erased by the fog, like the trees in a Chinese wall hanging—I experienced the house day-to-day as a crucible of magic.”

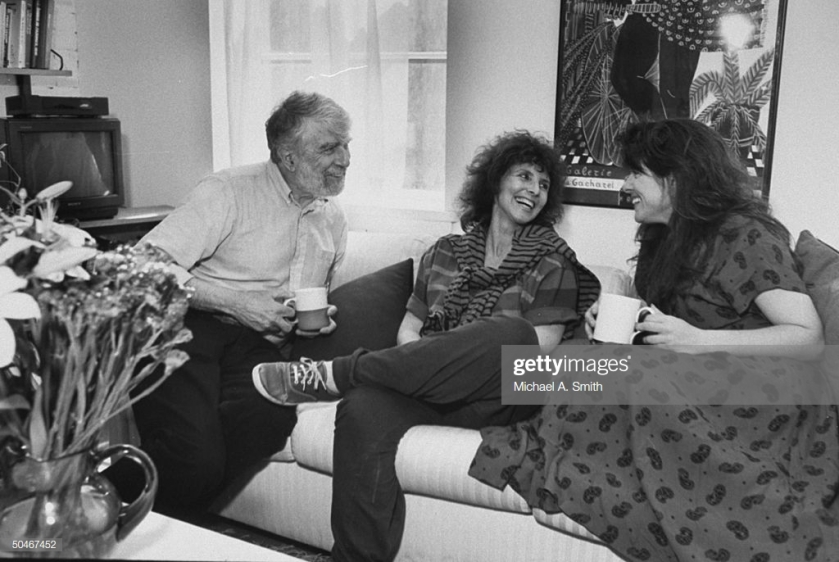

Here’s a photo, a family setting, of Leonard, his wife Deborah, and daughter Naomi (Photo credit: Michael A. Smith)

I had far less acquaintance with the house than she would, obviously, but I too found it magical. Yet, just as I found with Wright Morris, it was the one-on-one sessions in Leonard Wolf’s office–where we concentrated, together, on making my thesis project the best, most interesting “entity” we could—I felt were most valuable. Leonard Wolf was studying Russian at the time, and he suggested I include my own translations in my project, which I did: three poems by Alexander Blok (“Catkins,” “The Stranger” and “The Artist”), although we’d gone over a number of poems I had translated while taking lessons from our babysitter, Mrs. Pein. She’d given me language lessons in exchange for guitar lessons for her granddaughter—my reward if I did хорошо (good) after each lesson was not just one but two shots of vodka. At the time I felt I was being a fool (дурачить; durachit’), because, although I was able to read the poetry of Pushkin, Lermontov, and Pasternak in the original language, we focused mainly on grammar (I even wrote compositions for her which she “corrected.”). I did not learn to speak the language all that well—but a very constructive, positive result of the three years I spent working at the Lawrence Radiation Lab was, on my multiple bus journeys to and from work each day, I studied Russian, and by the time I met Leonard Wolf, I knew the language fairly well.

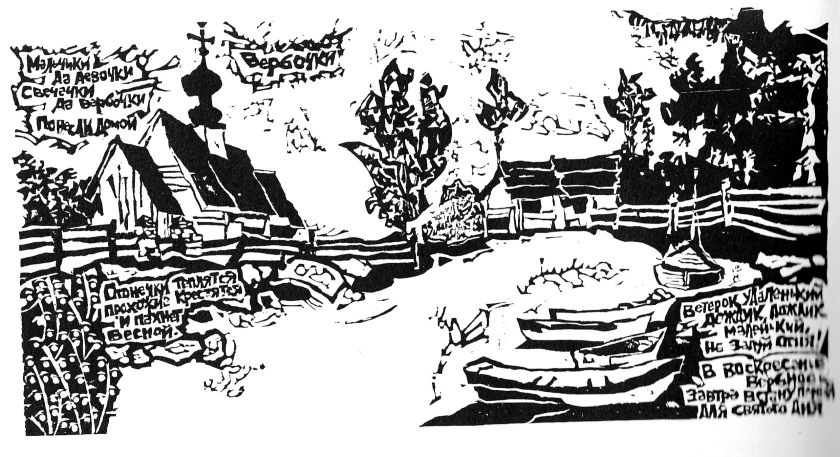

Here are two translations of Alexander Blok I made (with Leonard’s support and assistance–he was a stickler for finding just the “right” word–one word and one only—to “fit” the Russian)—two poems we would include in my final thesis manuscript:

[I am sorry to say this WordPress format will not reproduce the poems that follow as they appeared on the page, their exact form (lines indented, etc), so I will simply indicate the line breaks where they occur. We lose the visual counterpart, but at least we have the words–in correct order!]

THE ARTIST

In summer heat and snow-driven winters, / On the day of your wedding, feast, or funeral / I wish to rouse my deadly boredom with / The soft forgotten sound of bells.

Here! It is rising. With cold regard / I want to know, and fix, and strangle it. / Before my keen review the peal of bells / Extends to a barely perceptible thread.

Is the whirlwind rising from the sea? The bird / Of paradise singing in the leaves? Time swung / To a halt? The apples of May strewn with snow / Of blossoms? An angel passing in flight?

The hours pass, prolonged, bearing the world’s weight. / Sound, motion, and light expand; / The past passionately gazes at itself in the future. / No present. Nothing pathetic any more.

Finally, on its threshold of birth, the soul / –The new soul, the unknown force– / Is stricken by a curse, struck like thunder, / Conquered by creative reason, only to be killed.

He is locked within the frozen cage— / The gentle, kind, unbroken bird, / The bird that wished only to bear away death, / The bird that flew only to save the soul.

Here! This is my cage, of tempered steel / That glistens in the evening fire. / Here is my bird, formerly bright in plume, / Swinging on a hoop, singing in the window.

Its wings are clipped. It knows the song by rote. / Do you like to stand beneath the window? / The songs please you. But I, jaded and forlorn, / Long for more—and again, am bored.

THE STRANGER

On evenings above the restaurants / Densely lies the troubled air; / It holds the rancid breath of spring, / Conveying drunken calls—

Over the dust of by-lanes falls, / Toward the bored suburban flats, / The baker’s golden crest / And the shrill cries of children.

At night, beyond the city pikes /The dandies by the ditches stroll / With their ladies, tipping their derbies, /And exercise their wits.

Out on the lake the oarlocks creak, / A woman screams, /While in the city, bored with it all, / Indifferent, curls the moon.

On nights like this my only friend /Is the curved reflection in the glass, /Like I, befuddled / By the bitter sacramental wine.

In rows by tables close to mine / The drowsy waiters stand, / While drunks with rabbits’ eyes cry out, / “In vino veritas!’

Each night, at one suggested hour / –Do I dream, or do I see?– / The figure of a girl in silk / Passes by the window pane.

Then slowly, slight, she makes her way / Among the drunken men–alone– / As frail as smoke within the room, / And sits beside the window frame.

A vestal dressed for solemn rites: / Her skirts, like wine, excite, / Her hat with plumes among the smoke / And rings on every finger.

Strange: to watch her weave that spell / I see beneath a darkened veil; / Stranger still the promise held / Of veiled and distant shores.

The secret spell is mine to keep / –Deliverance in the sun– / Into the center of my soul / The wine and she have found their way.

I am turned on a spire of feathers– / My brain, like plumes, begins to sway— / Drawn by the blue, the glass of her eyes, / Its light on distant shores.

Now in my soul a treasure lies, / And I am keeper of the key! / In truth, O drunken prodigy, / I know in wine is truth!

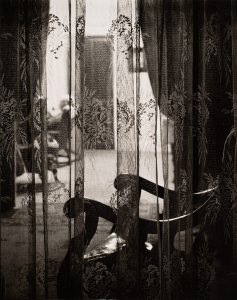

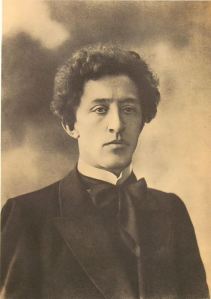

Here is a photo of Alexander Blok; a scroll painting I did of “The Stranger” (with Russian text); and a painting of another poem by Blok which I also translated: “This lamp, street, evening, shop, / This dim and senseless light of night– / If you should live another twenty years, / It will remain so. No end to it … You will die and begin again, go / Through it all again, as of old: / Evening, the icy fragments in the canal, / This lamp, this street, this shop.” (Photo credit: https://beautifulrus.com)

When it came to my own poems, Leonard Wolf was the perfect adviser, or “partner,” to have, for we thought along totally compatible lines when it came to the relationship of form to content. My training at Pratt Institute (anatomy classes coupled with life-drawing labs; rendering sessions, trompe l’oeil; design projects such as creating a living room based on color juxtapositions found in a favorite painting) had left me with much respect for formal properties in the visual arts (and the same in music: learning to play over set chord progressions long before I attempted “free jazz”). I had carried this respect for formal properties over when I started to write poetry—respect for the fundamentals.

I was thrilled by the “freedom” of Dylan Thomas’ poem “Fern Hill” (Line 1, 14 syllables; Line 2, 14 syllables; Line 3, 9 syllables; Line 4, 6 syllables; Line 5, 9 syllables; Line 6, 14 syllables; Line 7, 14 syllables; Line 8, 7 syllables; Line 9, 9 syllables. The lines are not arbitrary, for Thomas sticks to the set pattern in each stanza of the poem. Each stanza has the exact same number of lines with the exact same number of syllables in each line. I was thrilled by this mastery of craft (in spite of the poet’s drunken social habits), thrilled to find a host of words in the margins of his drafts, awaiting the selection, or choice, of just that “right” word–the inevitable word–for the poem.

I carried my respect for formal properties over into my own poems, and I would pay a price for it with certain factions at SF State, for “free verse,” or totally open, or “uncooked,” poetry, such as that practiced by the Beats, was still in vogue (a sort of Civil War, in fact, going on between open and closed form poets. More about that Civil War in a moment)—but Leonard Wolf was on my side. Again, In Naomi Wolf’s book, I found a very thorough, accurate, account of his ideas on the subject:

“Be disciplined. Do you want to know how to become a writer? It is not romantic. There is no revising a blank page. Keep going … [Naomi’s words]: “I remembered how, when I was a child, after I had told him I wanted to learn about them, he taught the standard forms of traditional poetry. Like a carpenter showing a child how to build a birdhouse, he taught me the basic shapes one could work with.” [quatrain, sonnet, ballad … and “the beats of the words”: iamb, trochee, spondee, anapest, dactyl, blank verse.] … “I would show him my latest poems—often written in the dreaded free verse, which was of course fashionable at the time … ‘Naomi, don’t paint abstractly until you can draw the figure. You can beak the form successfully once you have mastered it. Structure has to be the foundation—then you can play with it or depart from it altogether. But you have to know your craft … Emotions can be more powerful when they are closely confined by a strict form …The postwar poets I admired said that emotion, too, was a legitimate mode of thought. But the Beats made it a law that emotion would be the only mode of thought. They put feeling first and thought second. That led to disaster. I thought that was a pity, and I still do … The liberation of feeling and the discipline of form need each other. They need to be in balance.’”

Here is a poem of mine called “The Barmaid” we included in my thesis manuscript (I followed the syllable count of “Fern Hill” exactly—and even had the audacity to include rhyme!).

THE BARMAID

How could I ignore you, thinking of Renoir? / Like him, I’d trace your breast abed this frozen night. / I’m stirred with ginned regard. I know / Your skin would take the light. / But do I dare? Comme ci, comme ce, / I walk toward the phonograph – a crystal flue / Of winter sounds -and drop a dime. The trumpets snow / All floors with sleight; but you / Refuse my offer of a pas

De deux: ” For Sir, our management does not allow!” / So, let me tell you of your shoulders, how the sun / That frank, that unremembered glow / — “But Sir, I’m on the run?”– / Of light, would, be remembered now: / I’d put you in a field of wine and shade, and look / At you–just look at you–with the eyes of art, you know. / And what if eyes forsook / Their handwork for the nude below?

We’d sing hip, bone and breast while nestled in the grain / And drink the reddest wine and swim the dappled sun. / And stop to press our place of love / And sign it, just for fun. / But here? Blue-violet bodies strain / To cold and crowded sound, and no one sings. “Now Sir, / I’ve work to do, you’ll have to take a seat!” I shove / And shoulder from the girl, / Thinking Renoir would complain.

Here are three more poems we decided to include in the manuscript. The third, “Weekend,” would provide the title for the collection itself. A year after I graduated from San Francisco State College, and was teaching at the University of Hawaii, Carolyn Kizer, Editor of Poetry Northwest would accept “Weekend” for publication in the Autumn-Winter 1964-1965 issue of that journal—saying it “could be a major work”; and then, when she took the final version: “Congratulations on a noble effort.”

ANNIVERSARY: NUMBER SIX

I

We stomped, six years ago, the grass / Of churchyards with our love. / We shared our favorite trees, and felt / Our white within the greenfields move.

II

The flesh that broke you tore our youth / in two. Our white time fled / and left two howling naked lives, / twin secrets of a medieval bed.

III

You Jill, I learned to love; began / to love your kitchen: / the flowers you picked, the roses, pale, / and splintered glass you placed them in.

IV

Jack Thumb, a boy in corner, I / became. Vodka and caviar / my life; and kids who licked their lips / while I stained the frets of a small guitar.

V

If I were a sculptor I’d hoist your skirt; / a husband hold your hand. / I become either, a lover of sorts, / but seldom make the gesture bland.

VI

Guests in the doorway! Greet them well— / and if we have a fight /–open, flared when the moon comes up— / tell them, by God, we’ve earned the right!

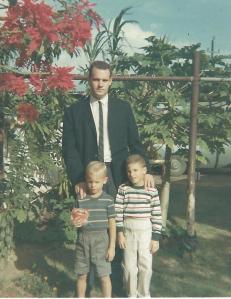

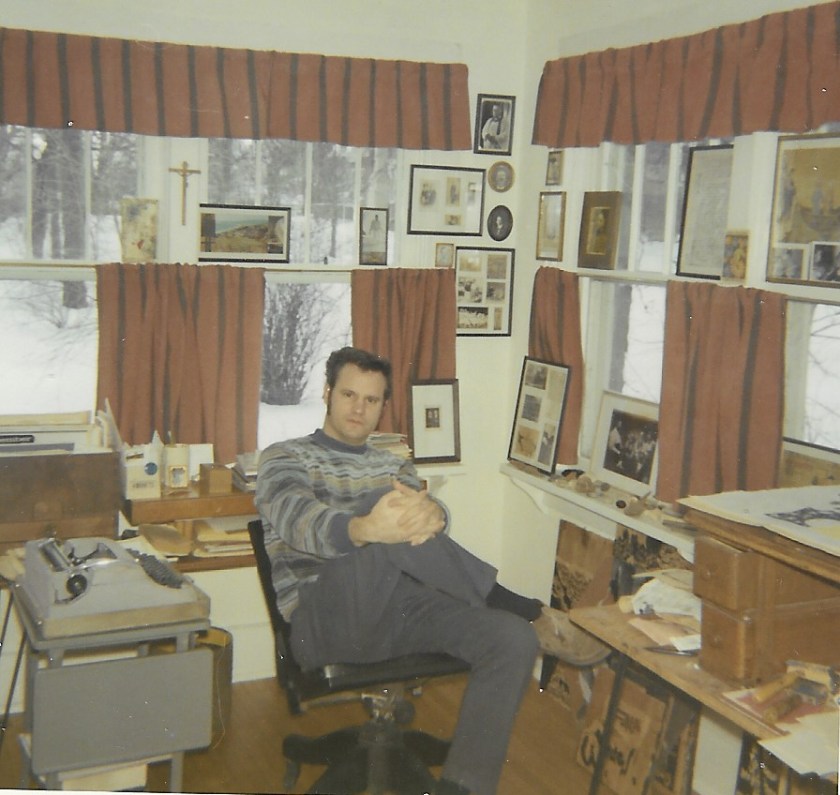

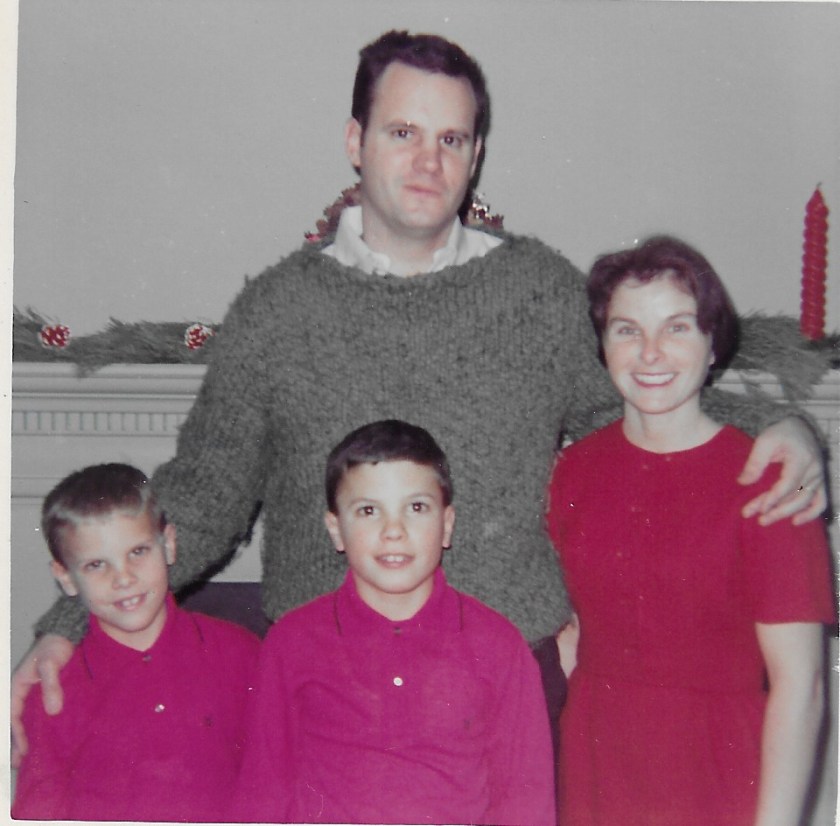

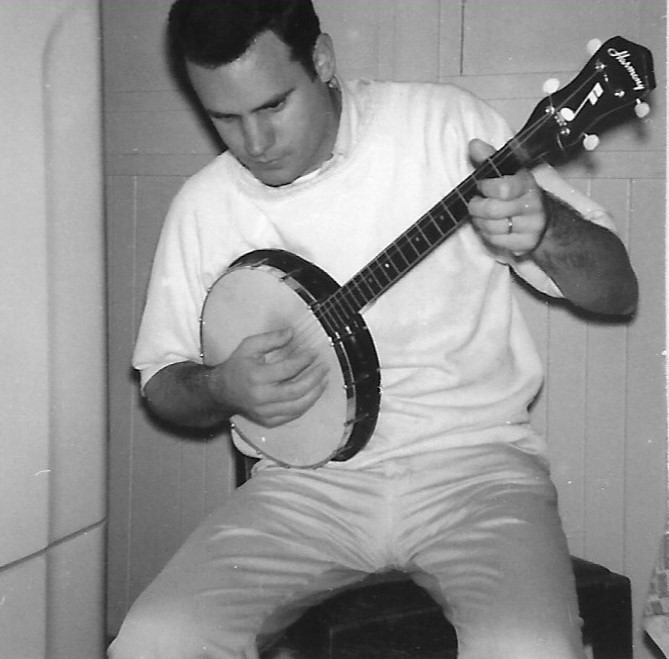

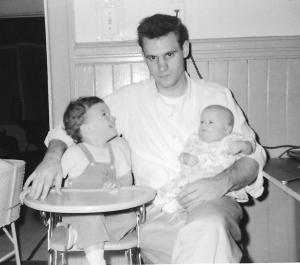

Here’s a photo of the (somewhat puzzled–“What have I done?”–maybe reluctant) young father depicted with his kids “who lick their lips” in the poem—and a full family photo, with Betty, taken at the same time:

PERSIAN MINIATURES

Pure form is like a nun who never works: / You will respect her chastity, but wish / That she would pray for you, or teach a child, / Or do some menial job among the sick. / By her work her grace is best exposed, / As in this world of rhythm and of shape / Where line is both itself and loving Persia.

Whose face and gilded horse peer over hills? / A man of valor and a thing of line. / This green umbrella tilts to make a shape / But also tilts to shade a Sultan’s head. / The light blue horse on which the monarch sits, / Surrounded by a galaxy of flowers, / Is music of the painter’s craft alone.

And more; for there the Sultan really sits, / Upon a horse whose midget feet reside / In fields of white and dark vermilion flowers. / This quiet work, in which each part is placed / To tell and yet transform the Sultan’s day, / Outshines the brightest flame, and makes one think / More secrets lie in fabric than in fire.

Pure form is like a nun without a church, /A Sultan who has lost his canopy.

WEEKEND

I

The faces of the street are your best friends: / The worried, blind, and weak; they come and go / And you are fond of them. You love the light / In laundromats, where many things are done: / You stop and see–who knows ?–what rough delight / In frayed machines, on working hands, in men. / –I’ve said a thousand times that we should move, / But nothing’s cheap, your mother knows– / Come home; your mother waits. We are involved / In time, and time derides your dalliance, /But cannot cast it out, as it did mine.

II

Perhaps the rank thorn is the separate will: / Today our eldest son plays Cain and strikes /

His two week brother at the breast. Good Cain, / My self, my child, why must we live like men? / We sulk and try to share a public park: / Its monody of color on the green, /

Its carrousel of lives. We eat above / And bide our time with talk and sandwiches. /

Yet when the boy returns from dirt to show / His wounded cheek, you send us off to join /

The children, fathers, lovers down below.

III

You call the ducks and give them crusts of bread; / I sit among the bland in hell. You stop / And listen, what to hear? My child, you know / But cannot say, and that is just as well. /

Deprived of lunch, I pass the row of blondes / Called mothers by their neighbors; hoist my son / Upon his small and honest seat, and watch / Him spin on iron gadgets in the sun. / One day we walked out early and he threw / Himself on dewy grass, who hadn’t been / Outside the house for days.

IV

It’s three o’clock. I’ve come for milk but sit / Beside the soft electric purr of our / New frigidaire, and drink the wine. It drums / –In vino veritas–a fever in my skin. / You stand beneath a single light and say, / “What reason brings you here?” The night, my dear, /

Is my best friend; and night and I shall have / A time, be ridiculed and ridicule– / Together purge our pity and our fear. / Sometimes I make you sick, you say. My dear, /

Sometimes my sickness makes me envy you.

V

“Matthew, Mark, Luke and John,” I sing– / And who are they? My boy, I cannot say, / But don’t they have fine names? I turn; you smile / And hug the boys, who tug upon your apron string. / Together by the sink, our forms imply / Four names in one, yet live alone. If I / Could often join the three of you, and keep / The truth that wine and night and I must bear, / I know we’d have a pretty thing; but dear, / Saturday night and Sunday too, / One does the work that one was born to do.

Here is the cover of Transfer 20, an anthology “representative of the best of the first nineteen years … intended as a celebration” published in 1965—an anthology which contained two of my own poems, “Persian Miniatures” and “The Barmaid”; and the cover of the issue of Poetry Northwest, 1964-1965 in which editor Carolyn Kizer would publish “Weekend.”

I took one more “literature” course in my last semester at San Francisco State College: a course in poet John Milton. Oddly, I do not recall who taught it. It may even have been Leonard Wolf—or Mark Linenthal? I will include, here, the last paragraph in a paper I wrote for the course, because it shows whatever progress I may (or may not) have made in my critical prose—and does illustrate what a “true believer” I’d become when it came to poetry. “An epic is the sum of the experience of all of its separate ‘books,’ or parts; of all of its metaphors, expostulations, and expulsions—correspondences, contrasts, and complexes. It may be a frieze or an ocean, but it has the unity of its adventure, and, in the case of Paradise Lost, the meaning is each grain of sand contained in the hourglass to which Milton committed it. And he would be the first person to remind us that those grains, like the parables of angels, are just a portion of the complete knowledge which we and poetry, as citizens of the City of God, are in a position to receive.”

I recently found another paper I wrote for that course: “Thought, Poetry and Theology,” in which I quote from Eric Heller’s The Disinherited Mind,” Meister Eckhart’s The Aristocrat, Miguel de Unamuno’s Tragic Sense of Life, and James Agee’s Let Us Now Praise Famous Men—and a draft of the final poem we would include in my thesis manuscript: a poem in ten parts called “A Letter to Friends in Alaska.” The “friends” were John and Margo Mitchell, whom I’d known in Hawaii when I first went there in 1956 (John was teaching English at the University, but quit to become a full time salmon fisherman in Alaska). The paper shows the extent of my reading at this time—even more extensive for I was also preparing, daily (and nightly) for my “orals” (which would accompany my thesis book of poems), orals to be administered by three professors: Leonard Wolf, James Schevill, and Bill Dickey. The orals would cover all of English literature from Beowulf to the present—so I had a fairly substantial list of books I was reading!

I was also taking a course called “Seminar in the Teaching of Writing”—in preparation for a job teaching I hoped to acquire upon graduation. And I was a teaching assistant for an undergrad composition course–one night a week–which meant I was “correcting” the first comp class papers I’d ever had to correct. I was very slow at it (“learning on the job,” so to speak). I called my “final” paper for the teaching seminar “Miss Lonelyhearts Among the Illiterates: a response to the remedial situation.” The last paragraph of this paper was not quite so positive as what I’d written John Milton’s poetry: “What is the mission of Miss Lonelyhearts, the ambivalent and diffident, the curious and affectionate teacher? First, perhaps, to tell his students not to be too easily sure of themselves, not to have too much poise.” [This strikes me now as an odd way to encourage the acquisition of ‘character;’ but also, it strikes me as vague. Was I encouraging “humility”?] “As for the English language, he would teach them to choose their words carefully, and remind them that the words they use—truth, death, desire—had not been easily won throughout history, and that, in an age of easy fulfillment such as our own, it was the teacher’s duty to keep them–in Philip Larkin’s phrase–from ‘fulfillment’s desolate attic.”

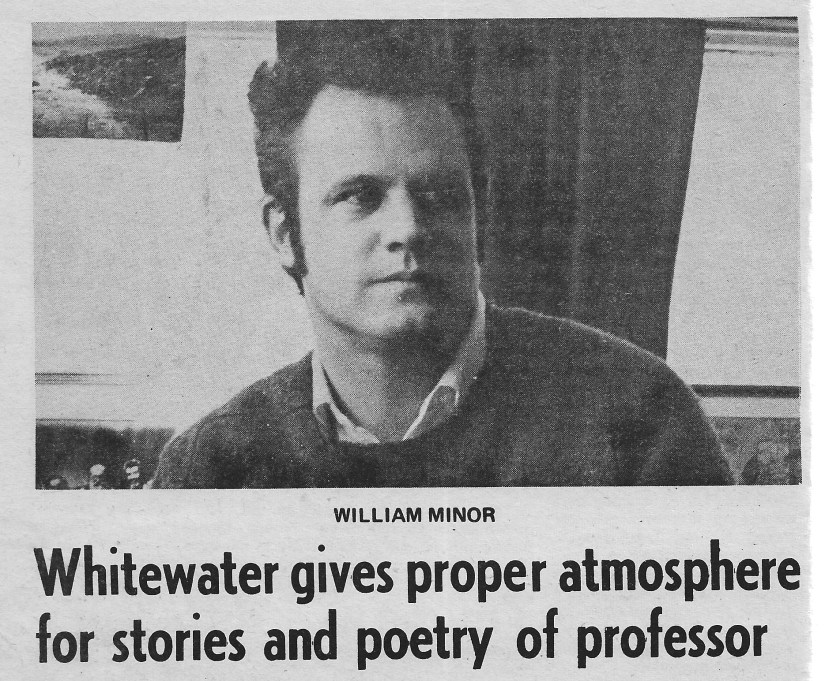

Before I turned in my poetry manuscript and suffered through my “orals,” something wonderful–a complete surprise–happened. I had three poems in the college literary journal, Transfer in 1963, and won the prize for BEST POEM, $25! The poem was “Persian Miniatures.” I was asked to accept the prize and give a “reading” at the Poetry Center. I’d never given a full-public reading of my work before. Here’s an account I would write years later of what took place.

“In 1962-63, I was a graduate student in Language Arts (Creative Writing) at what was then San Francisco State College. I was also a fairly recently ordained father (I had two kids under five years of age), a husband of sorts, and had been a full-time employee–a Scientific Data Analyst no less–at Lawrence Radiation Laboratory in Berkeley. I rode the bus to and from work every day, studying Russian (a portion of my M.A. thesis consisted of translations from Alexander Blok), and took classes at night. Needless to say, this was a hopping, hectic, nervous, but exciting time.

“I had some poems printed in Transfer 15, S.F. State’s literary magazine, and two of the editors were fellow students I never met: Ed Devlin and Paul Oehler. I won the twenty-five dollar annual poetry prize in ‘63, for a poem called “The Barmaid,” modeled on the intricate syllabic stanza patterns (and adding a rime scheme) of Dylan Thomas’ ‘Fern Hill.’ I was twenty-seven years of age, left work, attended classes, returned home, and was decidedly not a part of the campus literary scene. I was also so shy at the time that, accepting the prize and giving my very first poetry reading, I never even bothered to look up–thus missing my own boycott. ‘Beat’ students objected to a closed form or ‘cooked’ poem (as opposed to open and ‘raw’) having won the prize, and protested by raising a banner at the back of the hall–a gesture of dissent that, my then reticent and bashful consciousness buried in the task of reading my poem, I never witnessed.”

It’s all “true,” but something that surprises me now is that, according to this account, I was still working “full time” at the Rad Lab throughout the time I was at SF State, which strikes me as a nearly “impossible” thing to have brought off (given the course load I carried), although it is true that I was not “a part of the campus literary scene”—a situation that may have prompted the boycott. Years later (1971), I would have Ed Devlin as my office mate while teaching at Monterey Peninsula College, and I would finally meet, and become friends (we would do a book of poems together: Natural Counterpoint) with Paul Oehler, a superb poet.

“Poems: The Weekend” was accepted as “A creative work submitted to the faculty of San Francisco State College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Master of Arts.” My “orals” turned out to be another unanticipated “adventure.” I had assumed they would take place on campus, in a cheerless classroom or office, but on a sunny afternoon, I found myself walking alongside Leonard Wolf, Jim Schevill, and Bill Dickey down to Stonestown Shopping Mall.

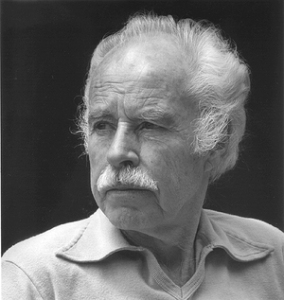

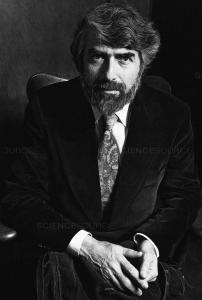

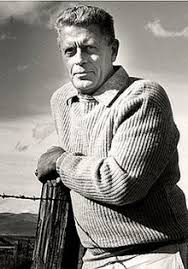

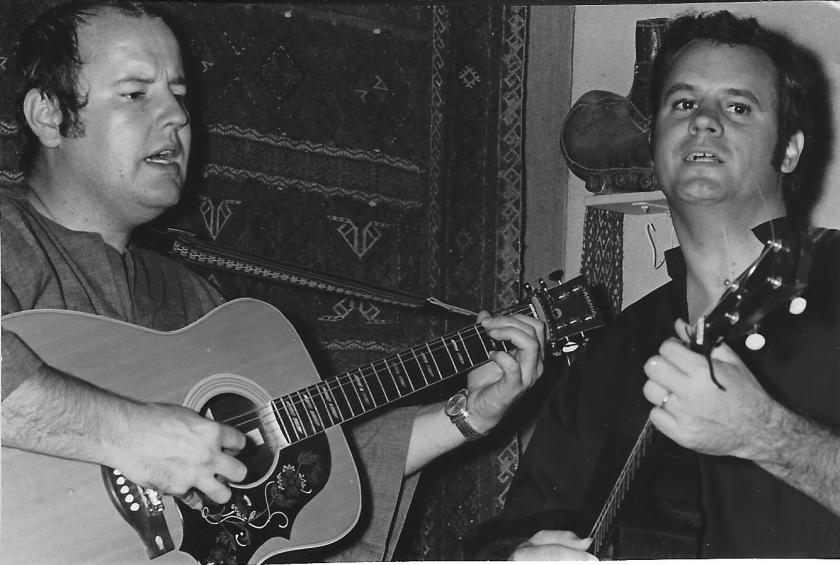

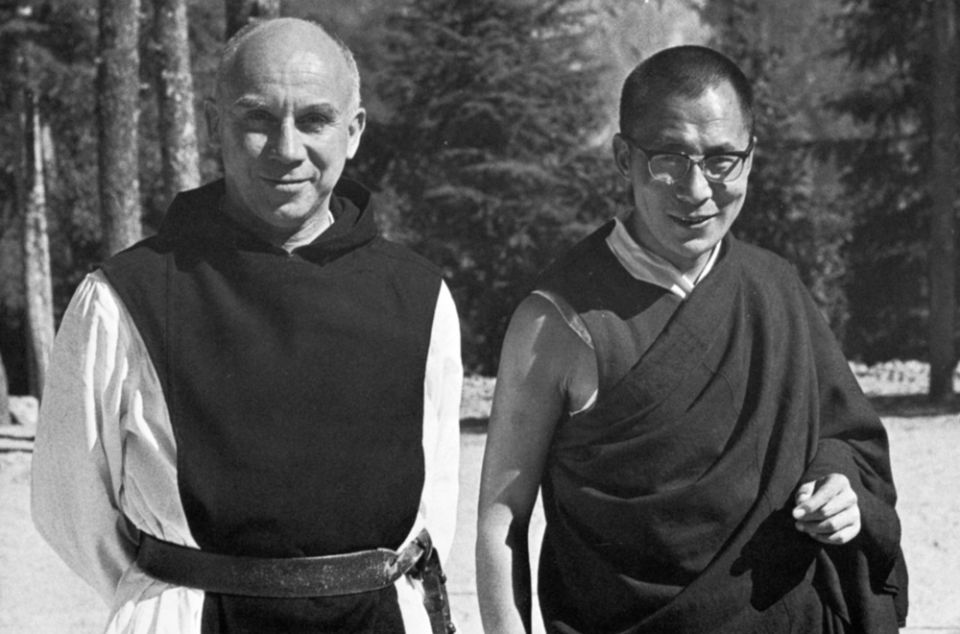

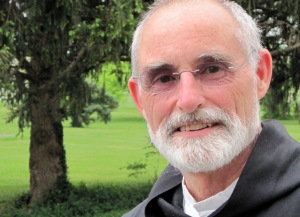

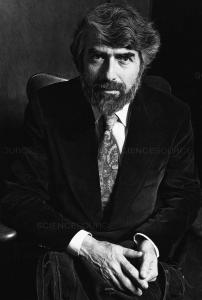

Here are photos of the three poets who would “grill me mercilessly” on the art form at a bar in Stonestown—when I thought I would “breeze through” the oral exam required for my Masters Degree: Leonard Wolf, Bill Dickey, and James Schevill: (Photo credits: www.sciencesource.com; Poetry Foundation; Goodreads)

I had applied to several colleges and universities for a job as an instructor (I’d heard, tentatively from the University of Hawaii, and I had even applied at SF State!). And I do recall feeling so confident about my prospects alongside my soon to be interrogators (or grand inquisitors) that I said, about a school I’d not heard from, “Well, if they’re not interested in me, I’m not interested in them!”–which must have prompted a response on the part of my three professors such as, “Good luck, you stupid cocky kid!”

They led me to a bar in Stonestown, and I thought, “Wow! This is going to be a piece of cake! A few drinks, a few laughs …”; but once we sat down and they asked what I might like to drink, they ordering nothing themselves. I declined their offer, thinking, “I’ll have a Cutty Sark on the Rocks–in honor of Hart Crane–when the celebration starts.” However, no celebration occurred for some time—about an hour and a half if I remember correctly. For that period of time, all three grilled me, mercilessly, on what seemed every aspect of English poetry. I don’t feel I did all that well on the academic and historically specific questions (“What is the difference in the way Wyatt and Surry first employed rhyme in their poems?”), and the thing that saved me was the poems I’d been memorizing each day—poems by everyone from Chaucer to John Keats to Dylan Thomas (and some poems in Russian and Classical and Modern Greek!).

The three professors left me sweating and devoid of a drink at the table while they excused themselves to determine my fate. When they returned, Jim Schevill told me I’d “passed,” and congratulated me–whereas Leonard Wolf whispered in my ear that the impressive recitations had saved my ass—if not exactly in those word, to that effect. Then all thee excused themselves to go home after another “hard day at the office,” I was left at the table–to order and sip my Cutty Sark on the Rocks, alone, lost, lonely–but greatly relieved.

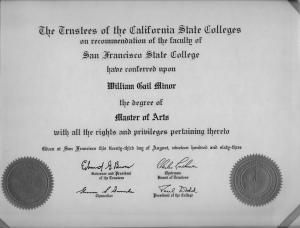

Here’s a signed copy of my thesis project, “Poems: The Weekend,” and my M.A. degree:

Ar last! I now had my Masters Degree in Language Arts (Creative Writing) from San Francisco State College, and I did receive an offer to teach at the University of Hawaii, for $5,500 a year. I’d been so impressed with the company I’d kept at SF State (heroes, idols such as Wright Morris and Leonard Wolf–the entire staff!) that I couldn’t sleep the night before I was to go in and tell them my decision regarding the future. I had actually decided (in spite of only “part-time” possibilities) to stay with San Francisco State College, if they let me—but when I told the hiring committee that I’d received an offer from the University of Hawaii, they all jumped up from their shares and grasped my hands in congratulations—and that was that.

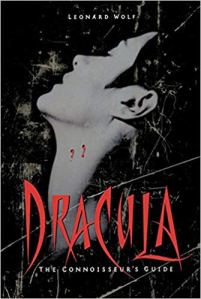

Leonard Wolf would leave San Francisco State College and go to New York in 1980. He would go on to publish several more books: A Dream of Dracula, Blood Thirst, 100 Years of Vampire Fiction (editor), Bluebeard : The Life and Crimes of Gilles De Rais, Dracula : the Connoisseur’s Guide, Horror – A Connoisseur’s Guide To Literature And Film, Monsters: Twenty Terrible and Wonderful Beasts From The Classic Dragon And Colossal Minotaur To King Kong And The Great Godzilla, The False Messiah, The Glass Mountain: A Novel (Overlook Press, 1993), The Passion of Israel, Vini-Der-Pu: A Yiddish version of Winnie the Pooh (Dutton 2000)—and others.

Leonard Wolf was ninety-six years of age when he passed away on March 20, 2019. I am very grateful to have known and worked so closely with this extraordinary man. Here are some of the books he published: (Photo credit: amazon.com)

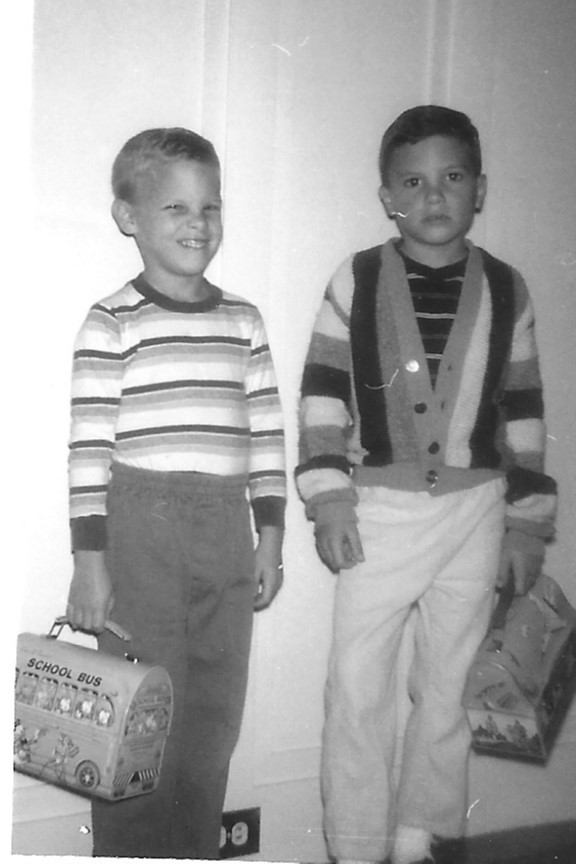

It seemed that, next thing I knew, my wife Betty and I had packed up our MacAllister Street home and she, Tim, Steve and I were literally sailing (on the President Wilson line) back to where marriage and family life had first started: the island of Hawaii, now an actual state in the USA since 1959.

I will close this post with three more photos: filming a lei-adorned Betty on board the President Wilson (about to sail to Oahu); my Betty looking very much at home in our new setting (the small backyard of an even smaller house we found on University Avenue), and the boys, Steve and Tim, with me in my dress code “uniform” (suit coat and tie in 1963—even in humid Hawaii!). But that–The Teaching at the University of Hawaii Years–is another tale I have to tell in the book length manuscript memoir I am at work on: “Unfolding: Aspirations and Attainments.”